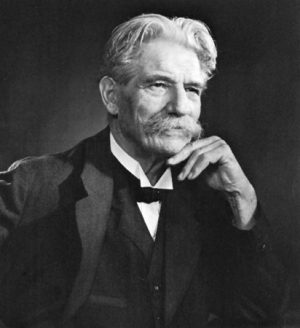

When you think of great humanitarians who left an indelible mark on history, Albert Schweitzer – Nobel Peace Prize Winner – stands tall. A towering figure in both the intellectual and humanitarian worlds, Schweitzer’s legacy stretches from the academic halls of Europe to the dense forests of Africa. This article explores his life, achievements, and lasting cultural impact. Whether you’re a student, traveler, or simply a curious mind, you’ll discover why Schweitzer remains a revered symbol of compassion and service.

Born in 1875 in the Alsace region, then part of Germany, Albert Schweitzer embodied the Renaissance ideal – philosopher, theologian, physician, and musician. His groundbreaking work in philosophy and musicology was only the beginning. Schweitzer’s decision to become a medical missionary in Africa captured the world’s imagination and earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952. His philosophy of “Reverence for Life” became a foundational ethic that continues to inspire cultural and humanitarian initiatives around the globe.

Germany’s rich tradition of humanitarianism, deeply rooted in its culture and history, finds a shining example in Schweitzer. To better understand Germany’s broader contributions to humanity, you might also explore Famous Germans: Icons Who Shaped the World.

Early Life and Education

Albert Schweitzer grew up in a devout Lutheran family in Kaysersberg. His early immersion in theology and music, particularly the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, laid the foundation for his dual career. He earned doctorates in both philosophy and theology from the University of Strasbourg, displaying an early penchant for crossing disciplinary boundaries – a rare trait even today.

Schweitzer also pursued an advanced study of organ music and became one of the leading authorities on Bach, publishing a major biography of the composer. His profound understanding of both religion and music provided him with a unique lens through which to view human experience and expression.

The “Reverence for Life” Philosophy

Perhaps Schweitzer’s most enduring contribution is his “Reverence for Life” ethic. Influenced by his studies of world religions and his work in Africa, he articulated a universal principle: all life is sacred and deserving of respect. This philosophy transcended religious, racial, and cultural boundaries and called for a deeper sense of empathy and moral responsibility.

His views contrasted sharply with the materialism and industrialization sweeping Europe in the early 20th century. Schweitzer argued for a life of service and simplicity, challenging individuals to consider their obligations toward other living beings.

If you’re interested in broader German ethical thought, our article on How German Philosophy Shaped the Modern World reveals how deeply ingrained ideas of morality and humanism are within German intellectual history.

Dr. Albert Schweitzer Playing The Organ In 1952

Lambaréné Hospital: A Legacy of Service

In 1913, Schweitzer and his wife, Hélène Bresslau, established a hospital in Lambaréné, now in Gabon. Combining Western medicine with a profound respect for local traditions, Schweitzer’s approach was ahead of its time. He worked tirelessly to expand the hospital despite war, disease, and scarce resources. His commitment made Lambaréné a beacon of hope and a model for future humanitarian efforts.

Life in Lambaréné was challenging. Schweitzer often performed multiple roles – physician, surgeon, administrator, and even builder. His writings from this period, such as “On the Edge of the Primeval Forest,” provide vivid, compassionate accounts of his work and the people he served.

World Wars and Continued Service

Schweitzer’s work was not insulated from global conflict. During World War I, he and his wife were interned by French colonial authorities due to their German citizenship. After their release, Schweitzer returned to Europe to raise funds and recover his health. Yet, even in Europe, he continued writing and advocating for peace.

Following the war, Schweitzer resumed his medical work in Africa, rebuilding and expanding his hospital. Throughout World War II, he maintained a neutral stance, focusing his energy on humanitarian service rather than political activism.

Winning the Nobel Peace Prize

In 1952, Albert Schweitzer was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his philosophy and humanitarian work. The Nobel Committee recognized not only his medical missions but also his profound moral leadership. In his Nobel lecture, Schweitzer issued a stark warning against the proliferation of nuclear weapons, stressing the need for an ethical revolution grounded in respect for life.

Rather than retiring into comfort, he used his Nobel Prize money to expand and modernize the Lambaréné hospital. Schweitzer continued his humanitarian efforts well into his eighties, proving that a life dedicated to service knows no retirement.

For readers interested in other German Nobel laureates and humanitarian figures, our profile on Otto Hahn – German Chemist offers another inspiring example.

Albert Schweitzer’s influence extends far beyond his lifetime. His “Reverence for Life” philosophy is now a cornerstone of many modern ethical debates, from animal rights to environmental conservation. Organizations worldwide, including Doctors Without Borders, cite Schweitzer as an inspirational forebear.

In education, Schweitzer’s teachings are included in curricula across disciplines, from philosophy and ethics to humanitarian studies. His work is often compared to other great humanitarians like Mother Teresa and Mahatma Gandhi, placing him firmly among the pantheon of global moral leaders.

Modern initiatives inspired by Schweitzer include awards, fellowships, and organizations dedicated to medical service and ethical leadership. The Albert Schweitzer Fellowship, for instance, supports hundreds of emerging professionals dedicated to health-related community service.

Moreover, Schweitzer’s life serves as a model for professionals today, illustrating that excellence in one’s field can – and perhaps should – be coupled with a commitment to humanitarian principles. Many modern medical missions, environmental movements, and ethical initiatives can trace their lineage back to the seeds Schweitzer planted.

If you would like to delve deeper into the background of notable German figures, our overview of Famous Germans will enrich your perspective.

Albert Schweitzer in Lambarene, 1933

Albert Schweitzer – Nobel Peace Prize Winner – remains an enduring symbol of compassion, intellect, and global service. His philosophy of “Reverence for Life” has become a timeless call to action, reminding us all of our responsibility toward one another and the planet. His life and work continue to inspire new generations seeking a more humane and just world.

Whether you’re a cultural enthusiast, student, or curious traveler, Schweitzer’s story offers a fascinating glimpse into Germany’s profound impact on global humanitarian efforts. Through his example, we are encouraged to lead lives marked by empathy, service, and respect for all living things.

Curious to learn more about remarkable German figures and traditions? Browse through our articles on Famous Germans, How German Philosophy Shaped the Modern World, and Famous German Scientists to deepen your knowledge!

Related articles:

Famous German Scientists Who Changed the World (Beyond Einstein!)