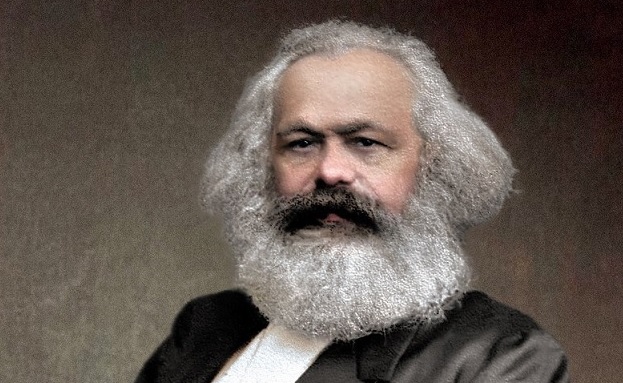

Few names provoke as much debate as Karl Marx. To some, he’s the visionary who exposed the injustices of capitalism and fought for workers’ rights. To others, he’s a controversial figure whose ideas inspired revolutions and reshaped global politics. Love him or loathe him, Karl Marx is undeniably one of the most influential thinkers of the 19th century – and his impact still echoes through economics, politics, sociology, and philosophy.

In this article, we’ll explore Marx’s life, core ideas, and enduring influence – while unpacking the myths and realities surrounding one of Germany’s most world-changing minds.

Marx’s Life – From Prussia to Political Exile

Karl Marx was born in Trier, Prussia in 1818 into a middle-class family. He studied law and philosophy at the universities of Bonn and Berlin, eventually earning a doctorate. Initially drawn to Hegelian philosophy, he soon began to challenge its idealism and instead embraced materialism. His academic ambitions gave way to radical journalism, where he critiqued the Prussian monarchy and capitalist society.

His political writings led to censorship and exile. Forced to flee from country to country, Marx finally settled in London, where he lived in poverty for much of his life. He was financially supported by his lifelong collaborator and friend Friedrich Engels. Their joint work resulted in two of the most influential texts in modern history: The Communist Manifesto (1848) and Das Kapital (Volume I published in 1867).

Historical Materialism – A New Lens on History

Marx proposed a revolutionary view of history known as historical materialism. Rather than focusing on great individuals or lofty ideals, he argued that history is shaped by the economic base – the way societies produce, distribute, and exchange goods. According to Marx, the material conditions of life determine the development of social institutions, legal systems, and even ideas.

He identified key stages in societal development: primitive communism, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, socialism, and finally communism. These transitions, he argued, were driven by conflict between social classes – primarily between those who own the means of production and those who sell their labor.

Class Struggle and Capitalist Contradictions

At the heart of Marx’s theory lies the class struggle. Under capitalism, the two dominant classes are the bourgeoisie (owners of capital) and the proletariat (working class). Marx contended that the capitalist system is inherently exploitative. Capitalists accumulate profit by paying workers less than the value of what they produce – this difference is what Marx called surplus value.

He argued that capitalism was riddled with internal contradictions: overproduction, underconsumption, financial crises, and worsening inequality. These systemic problems would, in Marx’s view, eventually lead to its collapse. The working class, increasingly impoverished and alienated, would rise in revolution to establish a classless society.

Alienation and the Human Condition

One of Marx’s more philosophical contributions is his theory of alienation, explored in his early writings. In capitalist societies, workers are alienated in four ways: from the product of their labor, from the production process, from other people, and from their own potential.

Instead of expressing creativity and purpose, labor becomes a mere survival mechanism. Marx believed that under socialism, labor would be transformed into a meaningful, social, and fulfilling human activity – a cornerstone of freedom and dignity.

Revolution, Praxis, and the Role of the Working Class

Unlike many philosophers, Marx wasn’t content with interpretation – he wanted transformation. His famous quote, “Philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it,” captures his commitment to praxis – the unity of theory and revolutionary action.

He believed that only the proletariat had the structural position to abolish class itself. But revolution was not inevitable; it required class consciousness – an awareness of shared exploitation and the political will to act collectively.

The Communist Manifesto – A Call to Action

Published in 1848, The Communist Manifesto was a concise, powerful declaration of Marx and Engels’ vision. It outlined the history of class struggle and described capitalism as a system that, while dynamic, was ultimately unsustainable.

Its most famous lines – “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles” and “Workers of the world, unite!” – became rallying cries for labor movements around the globe. The Manifesto argued for the abolition of private property, the centralization of credit and communication, and free education for all.

Das Kapital – Anatomy of Capitalism

Marx’s magnum opus, Das Kapital, is a detailed analysis of how capitalism functions – and why it fails. The first volume focuses on commodities, labor, surplus value, and the accumulation of capital. Though dense and complex, the work offers profound insights into economic dynamics that are still debated today.

Marx described capitalism as a vampire – feeding on living labor to generate profit. He used economic theory not to describe an ideal market but to reveal capitalism’s exploitative core.

Marx’s Influence – From the 19th Century to Today

- Politics: Marxism inspired revolutions in Russia, China, Vietnam, and Cuba. Though these movements often departed from Marx’s vision, they reshaped world history.

- Labor Movements: Unions and socialist parties across Europe and Latin America have drawn directly from Marx’s analysis.

- Sociology: His theories on ideology, power, and class remain central to critical sociology, especially the Frankfurt School and Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony.

- Economics: While mainstream economics rejected many of Marx’s conclusions, debates around income inequality, automation, and globalization often echo his concerns.

- Academia: Marxist thought continues to influence philosophy, literary theory, anthropology, and history.

Misunderstandings and Criticism

Marx has been both idolized and demonized. Critics argue that his ideas led to totalitarian regimes, mass violence, and economic collapse. Others accuse him of economic determinism – reducing human behavior to material conditions.

However, defenders of Marx distinguish between his original writings and later interpretations. They argue that Marx provided a framework for understanding power and inequality, not a rigid blueprint for governance. Even non-Marxist scholars acknowledge his enduring relevance in analyzing capitalism’s contradictions.

Karl Marx didn’t just write about the world – he changed it. His ideas continue to challenge how we think about power, labor, justice, and the future of economic life.

Whether you’re reading The Communist Manifesto, Das Kapital, or exploring modern critiques of capitalism, Marx offers not easy answers but a compelling framework for asking the most urgent questions of our time.

Want more German minds who shaped the world? Explore Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Martin Heidegger, and Arthur Schopenhauer.

Related articles:

How German Philosophy Shaped the Modern World

Exploring the Depths of German Philosophy

Famous Germans: Icons Who Shaped the World