Martin Luther is remembered as a revolutionary theologian, the spark behind the Protestant Reformation, and a man willing to defy the Catholic Church at great personal risk. But his greatest and most enduring contribution to the German-speaking world may not be theological – it’s linguistic. With one bold act of translation, Luther took a fragmented, dialect-divided linguistic landscape and gave Germans something they’d never had before: a shared written language that sounded like the people who used it.

In this article, we’ll explore how Luther’s 1522 translation of the New Testament into vernacular German helped lay the foundations of Modern Standard German. We’ll examine the social, cultural, and technological conditions that made it possible – and necessary – and we’ll trace how his work transformed not only language, but also literacy, identity, and nationhood.

The Linguistic Landscape Before Luther

Before Luther, “German” as a language was not unified. Instead, it was a patchwork of regional dialects, some of them so different from each other that speakers from different parts of the Holy Roman Empire couldn’t understand one another. These included:

- Middle Low German in the north

- Middle High German in the south and east

- A multitude of regional variants such as Swabian, Franconian, Bavarian, Saxon, and Alemannic

The educated elite wrote in Latin. Local clerks might use dialectal forms of written German, but there was no common written standard. Religious texts were in Latin, so ordinary people had limited access to scripture or theological ideas. Literacy itself was rare outside of monasteries and universities.

The Reformation: A Linguistic Opportunity

Luther’s break with the Catholic Church wasn’t only a spiritual event – it was also a political and cultural revolution. At its heart was a simple but radical idea: that ordinary believers should be able to read and interpret the Bible for themselves.

That idea had one major requirement: people had to understand the language in which the Bible was written. Luther believed strongly that faith came through hearing the Word of God – not in Latin, but in a language that common people actually spoke.

His mission wasn’t just to translate – it was to transform how people used German.

The 1522 New Testament: Clear, Rhythmic, and Real

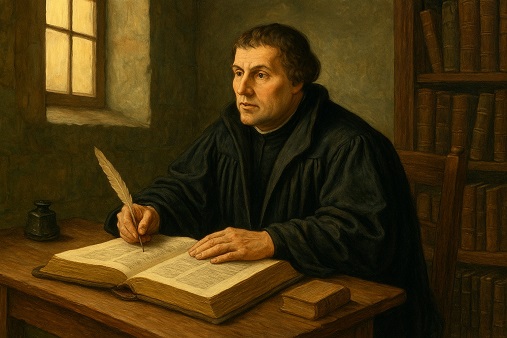

While in hiding at Wartburg Castle after being declared an outlaw, Luther translated the New Testament from Greek into German. He completed the initial translation in just 11 weeks, a feat that’s astonishing even today.

But what made his version unique was his method: he didn’t translate word-for-word from the Latin Vulgate. Instead, he worked from Greek and prioritized clarity, rhythm, and colloquial speech.

“You must not ask the Latin how to speak German,” Luther said. “We must ask the mother in the home, the children on the street, the common man in the market.”

This philosophy shaped every part of his translation. It wasn’t “church German.” It was living German – accessible, elegant, and musical. It felt like it was being spoken, not merely read.

Why Luther’s German Mattered

Luther used the East Central German dialect, particularly that of Saxony, which already had some prestige as the language of the Saxon chancellery. This form was somewhat understandable to both northern and southern Germans, making it a good base for broader comprehension.

Crucially, Luther’s choices in vocabulary, syntax, and phrasing helped normalize one variant of German over others. His translation acted as a kind of de facto linguistic standard – not enforced by law, but adopted by printers, preachers, and teachers who needed a clear, readable German text.

The Printing Press and Mass Distribution

Luther’s linguistic revolution would not have been possible without another 15th-century invention: the printing press.

The 1522 New Testament, often called the September Testament, was printed and distributed widely. It sold thousands of copies within weeks – an extraordinary number for the time.

For the first time, German speakers across different regions had access to a common text in a relatively uniform dialect. This began to stabilize spelling, grammar, and vocabulary.

Printers liked Luther’s German because it sold. Educators used it because it was clear. Preachers used it because it reached people. And over time, this “Lutherdeutsch” became the backbone of what we now call Modern Standard German.

The Old Testament and the Full Bible

Luther didn’t stop with the New Testament. Over the next 12 years, he worked with scholars to translate the Old Testament, publishing the full Bible in 1534.

This text was monumental – not just religiously, but linguistically. It included:

- A consistent orthography (by the standards of the day)

- A preface and marginal notes to explain theological points

- Biblical poetry rendered in graceful, lyrical German

The complete Bible became a linguistic and cultural cornerstone. It was read aloud in churches and homes, memorized by children, and quoted in sermons.

Impact on Literacy and Education

Luther’s translation didn’t just standardize the German language – it democratized it.

In Protestant regions, reading the Bible became essential. Families bought Luther’s Bible even if they owned no other books. This fueled a rapid expansion in literacy, especially among laypeople.

Schools in Lutheran territories began teaching reading and writing in German, rather than Latin. Over time, this educational reform shifted the linguistic center of German intellectual life from Latin to vernacular.

Cultural and Political Influence

Luther’s Bible also helped shape a shared sense of “German-ness.” Though political unification was still centuries away, the cultural cohesion fostered by a common language helped plant the seeds of nationalism.

Writers, poets, and philosophers adopted Luther’s German. His phrases entered common speech. His rhythm influenced later authors – from Goethe to Schiller. Even modern idioms often trace their roots to Luther’s biblical style.

Criticism and Linguistic Debate

Luther’s translation was not universally praised. Some conservatives objected to his bold language choices or felt he had altered theological meaning. Others disliked the idea of promoting vernacular over Latin.

Still, Luther welcomed linguistic debate. He saw language as a tool for communication – not a sacred relic. His approach was pragmatic: use what works, and what reaches the people.

Legacy in Modern German

Many phrases coined or popularized by Luther remain in use:

- “Perlen vor die Säue werfen” (casting pearls before swine)

- “Der Mensch lebt nicht vom Brot allein” (man does not live by bread alone)

- “Ein Herz und eine Seele sein” (to be of one heart and soul)

Luther’s impact goes far beyond the religious. He left a linguistic blueprint that modern German continues to build upon.

➡️ Learn more about the cultural role of language: From Poets to Politicians: German’s Role in Identity and Nation-Building

Martin Luther may not have set out to create a national language – but in pursuing clarity, relevance, and accessibility, he ended up doing just that. His Bible unified a patchwork of dialects into something closer to a common tongue. It brought written German to the people – and the people to the written word.

His linguistic choices helped shape the course of German literature, education, theology, and national identity. To this day, his German is still spoken – not just in churches, but in schools, books, and everyday life.

Luther didn’t just translate the Bible. He translated a culture.

Related articles:

➡️ The Evolution of the German Language: A Cultural History

➡️ The Birth of German: From Proto-Germanic to Old High German

➡️ Dialects vs. Standard German: Why Both Still Matter

➡️ From Poets to Politicians: German’s Role in Identity and Nation-Building

➡️ Global German: How the Language Travels the World Today