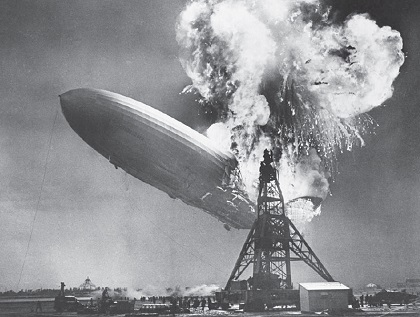

On the evening of May 6, 1937, the largest aircraft ever to fly approached its mooring mast at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in New Jersey, completing what should have been a routine transatlantic voyage. Within moments, the magnificent German passenger airship LZ 129 Hindenburg erupted into a towering inferno that consumed the 804-foot vessel in less than a minute, killing 36 people and horrifying witnesses who watched helplessly as passengers and crew leaped from the burning wreckage. The Hindenburg disaster, captured on film and immortalized by radio reporter Herbert Morrison’s anguished cry – “Oh, the humanity!” – became one of the 20th century’s most iconic catastrophes, effectively ending the era of passenger airship travel and serving as a potent symbol of technological hubris, human vulnerability, and the fragility of dreams.

The death of the Hindenburg represents far more than a tragic accident. This disaster occurred at a pivotal moment in history, when Nazi Germany sought to demonstrate technological superiority through spectacular civil aviation achievements, when transatlantic travel remained the privilege of the wealthy elite, and when humanity’s relationship with flight was still marked by wonder and ambition. The burning airship became a powerful metaphor for the illusions of the 1930s – the belief in inevitable progress, the faith in technology’s benevolence, and the conviction that human ingenuity could overcome natural limitations without consequence.

This comprehensive exploration examines the Hindenburg’s design and construction, the cultural significance of German airship technology, the circumstances surrounding the disaster, the competing theories about what caused the catastrophe, its immediate aftermath, and its lasting impact on aviation, popular culture, and collective memory. Understanding the Hindenburg disaster requires looking beyond the flames to see what this magnificent machine represented to the world it briefly dominated.

The Golden Age of German Airships: Context and Achievement

To understand the Hindenburg disaster’s significance, we must first appreciate the extraordinary achievement that German airship technology represented. Germany’s dominance in rigid airship development wasn’t accidental – it emerged from decades of innovation, investment, and a national commitment to lighter-than-air aviation that no other country matched.

The story begins with Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, the German military officer who pioneered rigid airship design in the late 19th century. Unlike non-rigid blimps, Zeppelin’s designs featured internal frameworks that maintained their shape regardless of gas pressure, allowing larger sizes and greater structural integrity. His first successful flight in 1900 launched an industry that would make Germany the undisputed leader in airship technology.

By the 1920s and 1930s, German airships had achieved remarkable success. The Graf Zeppelin, launched in 1928, completed over 590 flights including a round-the-world journey, carrying thousands of passengers safely across oceans. These voyages demonstrated that transatlantic air travel was not only possible but could be accomplished in luxury and relative comfort, crossing the Atlantic in less than half the time required by ocean liner.

German airship travel represented the ultimate in 1930s luxury transportation. Passengers aboard vessels like the Graf Zeppelin and later the Hindenburg enjoyed spacious lounges, comfortable sleeping cabins, fine dining with china and crystal, and observation decks offering spectacular views. The experience combined the elegance of ocean liner travel with the speed and modernity of aviation. For wealthy travelers, flying on a German airship represented the pinnacle of sophisticated international travel.

The Nazi regime, which came to power in 1933, recognized the propaganda value of German airship achievements. The Hindenburg and Graf Zeppelin were prominently featured in propaganda campaigns, their majestic flights presented as evidence of German technological superiority and national resurgence. The airships made propaganda flights over German cities, trailing swastika flags and broadcasting Nazi messages. This political appropriation would later complicate the disaster’s interpretation, adding layers of ideological meaning to what was fundamentally a technological catastrophe.

The Hindenburg itself represented the apex of airship design. Launched in March 1936, it was the largest aircraft ever built – 804 feet long, with a diameter of 135 feet, and containing over 7 million cubic feet of hydrogen gas. The passenger accommodations, located inside the hull, featured 25 small cabins, a dining room, lounge, writing room, and even a smoking room (carefully sealed and pressurized to prevent hydrogen from entering). The vessel could carry 50 to 72 passengers plus crew, crossing the Atlantic in about two and a half days compared to the five to seven days required by ship.

The Fateful Flight: May 6, 1937

The Hindenburg departed Frankfurt, Germany on May 3, 1937, carrying 36 passengers and 61 crew members on what was expected to be another routine transatlantic crossing to Lakehurst, New Jersey. The vessel had completed 63 flights, including ten round trips to the United States during the 1936 season, all without serious incident. Captain Max Pruss commanded the flight, with Ernst Lehmann – one of the world’s most experienced airship commanders – aboard as an observer.

The crossing proceeded uneventfully, though headwinds delayed the arrival by approximately 12 hours. As the Hindenburg approached Lakehurst on the evening of May 6, weather conditions were marginal – thunderstorms in the area had already delayed landing. Captain Pruss circled, waiting for conditions to improve. By early evening, the weather cleared sufficiently to attempt landing.

Ground crew members – approximately 200 naval personnel and civilian workers – assembled on the landing field, ready to grab the landing lines that would be dropped from the airship. Spectators gathered to watch the arrival, a common occurrence as airship landings attracted crowds fascinated by these enormous flying machines. Newsreel cameras filmed the approach, and radio reporter Herbert Morrison was on hand to record an audio description of the landing for later broadcast.

At 7:21 PM, as the Hindenburg approached the mooring mast at an altitude of about 200 feet, the crew dropped the landing lines to the ground crew. The vessel began valving hydrogen to reduce lift, preparing for the final descent to the mooring point. Everything appeared routine – a practiced procedure the crew had executed dozens of times before.

At 7:25 PM, witnesses observed a small flame near the top of the airship, toward the tail section. Within seconds, the flame erupted into a massive fire that engulfed the entire after section of the vessel. The Hindenburg’s tail dropped as hydrogen in the rear cells burned, and the airship began falling toward the ground, still moving forward. Passengers and crew inside felt a sudden shock, followed almost immediately by intense heat and the realization that the ship was on fire.

The descent took approximately 32 to 37 seconds from the first appearance of flame to the airship’s collapse onto the landing field. During those eternal seconds, people aboard made desperate decisions. Some jumped from heights of 100 feet or more, choosing the certainty of impact over burning alive. Others rode the ship down, escaping through windows and doors as it settled onto the ground, running through flames that consumed everything around them.

Ground crew and spectators rushed toward the wreckage despite the danger, pulling survivors from the burning debris. The hydrogen fire – burning with an almost invisible flame in daylight – generated intense heat but consumed itself quickly. Within minutes, the entire airframe had collapsed into a smoking skeleton of twisted metal. The disaster had unfolded so rapidly that newsreel cameras and Morrison’s audio recording captured the entire catastrophe, creating a documentary record that would become iconic.

The human toll was devastating yet, remarkably, not absolute. Of the 97 people aboard, 62 survived – 35 passengers and crew perished, along with one member of the ground crew. Many survivors suffered severe burns and injuries. That anyone survived such an inferno seemed miraculous; the survival of nearly two-thirds of those aboard suggested that the disaster, while horrific, could have been far worse.

The Investigation: Seeking Causes in the Wreckage

The Hindenburg disaster prompted immediate investigation by both German and American authorities. The U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Air Commerce convened a formal inquiry, while Germany dispatched its own investigative team. Both investigations faced the challenge of determining what caused the fire from wreckage that had been almost completely consumed.

The official investigations converged on several key findings. The airship had been electrically charged by flying through the storm front, creating a significant difference in electrical potential between the ship and the ground. When the wet landing lines contacted the ground, they provided a path for electrical current, effectively grounding the ship. This grounding, the investigators theorized, could have created a spark that ignited leaking hydrogen.

But why was hydrogen leaking? The investigation suggested that sharp turns during the landing approach might have caused a bracing wire to snap, puncturing one or more of the gas cells in the tail section. Hydrogen escaping from this rupture would have accumulated in the space between the gas cells and the outer cover, creating a highly explosive mixture. When a spark occurred – whether from static electricity, St. Elmo’s fire, or some other ignition source – this hydrogen-air mixture exploded.

The outer fabric covering also drew investigative attention. The Hindenburg’s exterior was covered with a fabric skin treated with a compound containing cellulose acetate butyrate, iron oxide, and aluminum powder – a mixture designed to tighten the fabric and provide weather protection. Some investigators noted that this coating was highly flammable and might have contributed to the fire’s rapid spread.

However, the official conclusion that the disaster resulted from accidental causes has never satisfied everyone. Alternative theories emerged almost immediately and have persisted for decades, suggesting sabotage, structural failure, or other causes beyond simple accident.

Theories and Controversies: Was It Really an Accident?

The Hindenburg disaster has generated persistent controversy regarding its cause, with alternative theories challenging the official accident conclusion. These competing explanations reflect not just technical disagreements but also the political context of 1937 and humanity’s tendency to seek intentional causes for catastrophic events.

The Sabotage Theory emerged almost immediately and has maintained adherents for decades. This theory suggests that an anti-Nazi saboteur – possibly a crew member or someone with access to the airship – deliberately caused the fire to strike a blow against the Nazi regime. Proponents note that the Hindenburg was a prominent Nazi propaganda symbol, making it a tempting target. They point to suspicious circumstances: an anonymous bomb threat received before departure, the inexplicable delay in investigation of certain crew members, and the convenient destruction of evidence in the fire.

The most detailed sabotage theory was advanced by A.A. Hoehling in his 1962 book, which suggested that rigger Eric Spehl, who died in the disaster, planted a bomb to sabotage the Nazi propaganda machine. Hoehling theorized that Spehl, who allegedly had a Communist girlfriend, placed a small explosive device in the area where the fire started. However, this theory relies heavily on circumstantial evidence and speculation about Spehl’s political views and personal relationships.

Critics of the sabotage theory note several problems: No hard evidence of sabotage was ever found, the investigation found no sign of explosive damage, and the political risk of attacking a vessel carrying innocent passengers seems unlikely for an effective saboteur. Additionally, both German and American investigators – who had different political interests – concluded the fire was accidental, making a cover-up unlikely.

The Incendiary Paint Theory gained prominence through the work of retired NASA scientist Addison Bain, who argued in the 1990s that the disaster was primarily caused by the flammable coating on the airship’s fabric skin rather than the hydrogen. Bain conducted experiments showing that the aluminum-based coating could burn rapidly and suggested that the hydrogen fire was secondary to the fabric fire.

This theory generated significant attention, even influencing a 1997 documentary that suggested the Hindenburg disaster had been misunderstood for decades. However, the incendiary paint theory has been thoroughly debunked by subsequent research. Detailed analysis showed that while the coating was indeed flammable, it couldn’t account for the observed burning pattern. The fire clearly originated inside the airship, not on its surface, and the coating’s burn rate was too slow to explain the rapid destruction. The visible orange flames in photographs came from burning fabric and other materials, not the nearly invisible hydrogen flame.

The Structural Failure Theory suggests that structural weakness or failure – perhaps a broken wire or torn gas cell – caused a hydrogen leak that then ignited through some means. This essentially elaborates on the official finding, emphasizing mechanical failure as the root cause rather than any environmental or electrical factor.

The St. Elmo’s Fire Theory proposes that the electrical phenomenon known as St. Elmo’s fire – a coronal discharge that can occur on pointed objects during electrical storms – created the ignition spark. This theory aligns with the investigation’s findings about electrical charging but suggests a specific mechanism for ignition.

Modern analysis, utilizing computer modeling and contemporary materials science, generally supports the investigation’s original conclusion: the disaster most likely resulted from a hydrogen leak ignited by an electrical spark in the charged atmosphere following the storm. While the exact sequence remains uncertain, the fundamental cause – hydrogen ignition – is not seriously disputed by mainstream researchers.

Immediate Aftermath: The World Responds

News of the Hindenburg disaster spread rapidly across the globe, carried by the very mass media technologies – radio and newsreels – that had documented the catastrophe. Herbert Morrison’s emotional audio recording, broadcast the next day, brought the disaster into American homes with unprecedented immediacy. His anguished commentary – “It’s burst into flames! … Oh, the humanity and all the passengers!” – became one of the most famous pieces of broadcast journalism in history.

Newspaper headlines worldwide proclaimed the tragedy. The dramatic newsreel footage appeared in cinemas within days, ensuring that millions witnessed the airship’s destruction. These images became immediately iconic – the massive vessel engulfed in flames, tiny figures leaping from the wreckage, the collapsed skeleton smoldering on the landing field. The disaster captured public imagination in ways that previous aviation accidents had not, partly because of the dramatic visual documentation but also because airship travel had seemed so safe, so established, so representative of technological progress.

The German government faced a propaganda disaster. The Hindenburg had been a symbol of Nazi technological achievement and national pride. Its destruction – broadcast globally – was a humiliating setback. German authorities initially tried to control the narrative, suggesting sabotage by anti-Nazi elements, but the international investigation’s findings of accidental causes undermined these efforts.

Public confidence in airship travel evaporated almost overnight. The disaster demonstrated that hydrogen airships, despite years of safe operation, carried inherent catastrophic risk. Even one disaster was enough to destroy the industry. Passenger bookings collapsed, and the era of commercial airship travel effectively ended on that May evening in Lakehurst.

The End of an Era: Why Airships Never Recovered

The Hindenburg disaster is often cited as the event that ended the airship era, but this explanation oversimplifies a more complex story. While the disaster delivered a devastating blow to public confidence, multiple factors ensured that passenger airships would never recover their prominence.

The fundamental problem was hydrogen. Helium – the safe alternative – was expensive, scarce, and largely controlled by the United States, which refused to export it for political and military reasons. Without helium, passenger airships remained inherently dangerous. A single catastrophic failure, which had seemed like a remote possibility, had proven to be devastatingly real.

Economic factors also worked against airships. By the late 1930s, fixed-wing aircraft were rapidly improving in range, speed, and passenger capacity. The Boeing 314 flying boats, introduced in 1938, could cross the Atlantic with 74 passengers, matching airship capacity while being faster and less vulnerable to weather. The economics increasingly favored airplanes over the massive infrastructure required for airship operations.

World War II accelerated aviation technology development while ending civilian airship programs entirely. The Zeppelin works were repurposed for military production. By war’s end, aircraft had so thoroughly surpassed airships in every practical measure that reviving passenger airship service made no economic sense.

Post-war airship development focused on non-rigid blimps for advertising, surveillance, and specialized applications. These small, helium-filled blimps shared only superficial resemblance to the majestic rigid airships of the 1930s. The era of intercontinental passenger airship travel had ended permanently, a casualty of the Hindenburg disaster and the technological progress it helped accelerate.

The Disaster That Defined an Era’s End

The death of the Hindenburg on that May evening in 1937 represented far more than the tragic loss of 36 lives or the destruction of a magnificent machine. The disaster symbolized the end of an era – not just in aviation technology but in a broader sense of pre-war optimism about human progress and technological mastery. The burning airship became an icon of catastrophe precisely because it represented so much: German technological achievement, luxury travel’s golden age, humanity’s conquest of the air, and the 1930s’ faith in progress.

The disaster’s exceptional documentation ensured its place in collective memory. Morrison’s anguished narration and the dramatic newsreel footage created a visceral record that remained powerful across generations. These images and sounds became the template for how people visualized catastrophic failure – sudden, spectacular, and consuming everything it touched.

For Germany, the disaster carried particular weight. The Hindenburg had been a source of national pride and Nazi propaganda. Its destruction was both a practical disaster for the Zeppelin company and a symbolic blow to the regime’s technological prestige. In hindsight, the burning airship seems almost prophetic—a spectacular failure foreshadowing the far greater catastrophe that Nazi Germany would bring upon itself and the world.

The Hindenburg disaster effectively ended commercial airship travel, though whether this represented tragedy or inevitable technological evolution remains debatable. Airships were already being surpassed by fixed-wing aircraft; the disaster simply accelerated this transition while ensuring it would be dramatic and memorable rather than gradual and forgotten.

More than eight decades later, the Hindenburg disaster retains its hold on popular imagination. It remains a powerful reminder that technological achievement and human ambition always carry risk, that progress is never as inevitable or secure as it appears, and that single moments can change everything. The burning airship symbolizes not just a specific disaster but the universal human experience of watching dreams and achievements consumed by forces beyond control.

In our contemporary age of rapid technological change and ambitious engineering projects, the lessons of the Hindenburg remain relevant. The disaster reminds us to respect the power of nature, to design with worst-case scenarios in mind, to maintain appropriate humility about human mastery of technology, and to remember that confidence built on success can be shattered in moments.

The magnificent airship that burned at Lakehurst represented humanity’s soaring ambitions and the terrible cost of their failure – a lesson written in flame against the New Jersey sky, captured in that eternal cry: “Oh, the humanity!”

Related articles:

German Zeppelin: The Rise and Fall of Germany’s Giant Airships

How the German Zeppelin Worked: Inside the Engineering of Airship Giants

Transportation Future

Zeppelin Airships

Zeppelins the Bombers