The left-wing Red Army Faction (Rote Armee Fraktion–RAF) became internationally known through its bloody exploits in West Germany and through its contacts with terrorist groups in other countries. The RAF was an outgrowth of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, which held up banks, bombed police stations, and attacked United States army bases in the 1970s. By 1975 some ninety members of the gang were in custody. In the middle of her trial in 1976, Ulrike Meinhof, one of the RAF ringleaders, committed suicide in prison. Another member, Andreas Baader, was sentenced to life imprisonment, but in 1977 he too took his own life in prison.

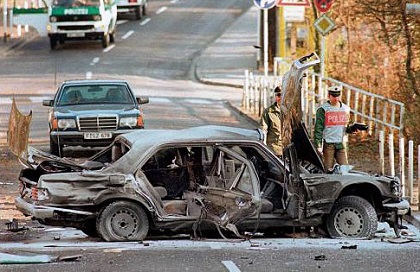

By the early 1980s, the original leaders of the RAF had been succeeded by a new and equally violent group that was Marxist-Leninist in orientation and saw itself as part of an international movement to topple the power structures of the capitalist world. A core group of twenty to thirty terrorists carried out the most deadly operations of the RAF. Periodic attacks were mounted against United States and NATO military leaders and bases and against prominent German officials and businesspeople. Demonstrations were held throughout the country to support a hunger strike by RAF prisoners and to protest the introduction of intermediate-range ballistic missiles. RAF violence had declined somewhat by 1990, although the RAF and other left-wing radical groups like the Revolutionary Cells carried out attacks against United States government and business targets. In November 1989, the chief executive of the Deutsche Bank, Alfred Herrhausen, was assassinated. In April 1991, Detlev Rohwedder, the director of the Treuhandanstalt (Trust Agency), the mammoth agency charged with privatizing East German state enterprises, was murdered by terrorists with connections to the Stasi. In August 1992, the RAF published a lengthy statement admitting past errors and announcing a decision to suspend the strategy of violence in carrying on its struggle.

By the early 1990s, attention had shifted to violence by neo-Nazi and other right-wing fringe groups. The fanaticism of the xenophobic rightists was fueled by the presence of large numbers of foreign workers and by the increasing number of aliens seeking political asylum in the country. Legal but extreme right-wing parties such as the German People’s Union (Deutsche Volksunion–DVP) and the Republikaner (Die Republikaner–REP) maintained their legal status by avoiding Nazi symbols and propaganda and keeping their distance from smaller neo-Nazi groups. With members numbering mostly in the low hundreds, the latter tended to be splintered and indistinct, which helped them evade bans and government surveillance.

Right-wing extremism found new supporters in the wake of the unemployment and turmoil that accompanied German unification. In both the eastern and western parts of Germany, outbreaks of violence were sparked by the growth of racial and ethnic intolerance. The federal police reported 2,285 acts of rightist violence in 1992, a sevenfold increase over the number reported in 1990. Seventeen deaths resulted. The greatest number of perpetrators were youths under the age of twenty. The police count of known right-wing extremists, estimated at some 40,000 in the early 1990s, slightly exceeded the estimated number of left-wing extremists. Some 6,400 of these extreme right-wingers were considered prone to violence. Their attacks were directed against asylum-seekers, migrants from Eastern Europe, nonwhites, and in some cases homosexuals, prostitutes, and members of the former Soviet armed forces. Some of the most serious outrages, such as street assaults and firebombings of hostels for foreigners, occurred in gritty eastern industrial centers–Rostock, Chemnitz, Cottbus, and Leipzig. The west, however, was not immune to such violence, and deaths occurred in bombing incidents in Moelln in late 1992 and in Solingen in mid-1993.

The police were accused of responding slowly when hostel residents were threatened and of treating neo-Nazis too gently, often releasing without charge those allegedly involved in terrorizing hostel-dwellers. Courts handed down mild sentences, in most cases probation or brief jail terms. Western police units had to be deployed to the eastern region to help control the violence. Under pressure to act more forcefully, the federal police raided premises occupied by the neo-Nazis to gain evidence to suppress them. In December 1992, the federal Ministry of Interior banned four small neo-Nazi groups and also placed the Republikaner under observation to determine whether the organization could be banned as undemocratic under the constitution. A new federal police division to monitor and repress rightist violence was also announced at that time.

These actions soon bore fruit, and in 1993 the number of deaths caused by right-wing violence fell to eight and declined still further in 1994. Tough sentences on right-wing extremists acted as a deterrent to violence, and a tightening of the country’s liberal asylum law in May 1993 reduced social tensions about the large number of foreigners living in Germany.

International terrorist organizations are represented among several of the colonies of workers and asylum-seekers in Germany. Although more than 2 million Muslims from Turkey, the Middle East, and North Africa live in the cities of western Germany, only a tiny minority can be considered political extremists. In the 1980s, members of the Palestinian groups Hizballah and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command had been involved in airline hijackings and attacks on United States service members. During the same decade, members of the Kurdish Workers’ Party bombed and staged violent protests at the offices of the Turkish government in Germany, and the Provisional Irish Republican Army carried out several attacks against British military targets in Germany. The number of incidents of international terrorism abated during the late 1980s and the first half of the 1990s, however, in part because of more determined investigation and prosecution of international terrorism by the German police and judiciary authorities.

| Known terrorist groups in Germany (both active and in-active) | |||

| Right Wing Extremists | Anarchists and Left Wing Extremists | Islamists and Salafists | Separatists and Nationalists |

| Atomwaffen Division since 2018 | Red Army Faction 1970–1998 | Al-Qaeda since 2006 | Provisional Irish Republican Army |

| Freikorps Havelland 2003-2005 | Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine | Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant since 2015 | Black September |

| Gruppe Freital 2015-2018 | Revolutionary Cells 1973–1993 | ||

| National Socialist Underground 1999-2011 | Anti-Imperialist Cell 1992 – 1995 | ||

| Deutsche Aktionsgruppen 1980 | Movement 2 June 1972–1980 | ||

| Wehrsportsgruppe Hoffman 1973-1980 | Tupamaros West-Berlin (and Munchen) 1969-1970 | ||

| Combat 18 since 1990’s | Revolutionäre Aktionszellen (RAZ) 2009-2011 [9] | ||

| Action Front of National Socialists/National Activists 1977-1983 | Rote Zora 1974 – 1995 | ||

| Revolution Chemnitz 2018-2019 [10] | Militante gruppe 2001-2009 | ||

Related articles:

National Security in Germany

Prussia’s Emergence as a Military Power

Creation of the Bundeswehr

The German Military in Two World Wars

Bundesheer

Bundesmarine

Luftwaffe

Military Justice in Germany

German Uniforms, Ranks, and Insignia

Foreign Military Relations

Internal Security

Land Police Agencies

Federal Police Agencies

Police Agencies in Germany