The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, a pivotal event in ancient history, marked a significant turning point in the Roman Empire's expansionist ambitions. In 9 AD, an alliance of Germanic tribes, led by Arminius, a chieftain of the Cherusci tribe, ambushed and decimated three Roman legions commanded by Publius Quinctilius Varus. This battle, fought … [Read more...]

The Holy Roman Empire: An Epoch of European History

The Holy Roman Empire, often deemed a paradoxical entity, was a multi-ethnic complex of territories in Western, Central and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars. Despite the anachronistic association with Rome, the Empire was a distinctly European polity … [Read more...]

Opening of the Berlin Wall and Unification

November 9, 1989 will be remembered as one of the great moments of German history. On that day, the dreadful Berlin Wall, which for twenty-eight years had been the symbol of German division, cutting through the heart of the old capital city, was unexpectedly opened by GDR border police. In joyful disbelief, Germans from both sides climbed up on the … [Read more...]

The Weimar Republic, 1918-33

The Weimar Republic, proclaimed on November 9, 1918, was born in the throes of military defeat and social revolution. In January 1919, a National Assembly was elected to draft a constitution. The government, composed of members from the assembly, came to be called the Weimar coalition and included the SPD; the German Democratic Party (Deutsche … [Read more...]

Bismarck and the Unification of Germany

Liberal hopes for German unification were not met during the politically turbulent 1848-49 period. A Prussian plan for a smaller union was dropped in late 1850 after Austria threatened Prussia with war. Despite this setback, desire for some kind of German unity, either with or without Austria, grew during the 1850s and 1860s. It was no longer a … [Read more...]

The Thirty Years’ War

Germany enjoyed a time of relative quiet between the Peace of Augsburg, signed in 1555, and the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War in 1618. The empire functioned in a more regular way than previously, and its federal nature was more evident than in the past. The Reichstag met frequently to deal with public matters, and the emperors Ferdinand I (r. … [Read more...]

The Protestant Reformation

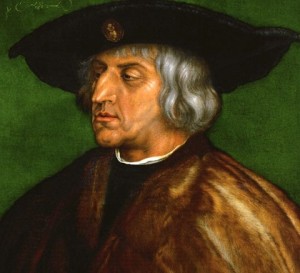

On the eve of the Protestant Reformation, the institutions of the Holy Roman Empire were widely thought to be in need of improvement. The Habsburg emperors Frederick III (r. 1440-93) and his son Maximilian I (r. 1493-1519) both cooperated with individual local rulers to enact changes. However, the imperial and local parties had different aims, the … [Read more...]

Medieval Germany – The Merovingian Dynasty, ca. 500-751

The Merovingian Dynasty, reigning from approximately 500 to 751, is often heralded as the foundational ruling family of medieval Germany and much of Western Europe. This article delves into the origins, significant achievements, and enduring legacy of the Merovingians, whose influence was instrumental in shaping the early medieval landscape. … [Read more...]