Karl Friedrich Hieronymus Freiherr von Münchhausen, also known as “the baron of lies” (born May 11, 1720, Bodenwerder, Hanover – died February 22, 1797, Bodenwerder), initially served as a page to Prince Anton Ulrich von Braunschweig, and later as a cornet, lieutenant and cavalry captain with a Russian regiment in two Turkish wars. In 1760 he retired to his estates as a country gentleman.

Karl Friedrich Hieronymus Freiherr von Münchhausen, also known as “the baron of lies” (born May 11, 1720, Bodenwerder, Hanover – died February 22, 1797, Bodenwerder), initially served as a page to Prince Anton Ulrich von Braunschweig, and later as a cornet, lieutenant and cavalry captain with a Russian regiment in two Turkish wars. In 1760 he retired to his estates as a country gentleman.

He became famous around Hannover as a narrator of extraordinary tales about his life as a soldier, hunter, and sportsman. After the death of his first wife, Münchhausen married a 17-year old noblewoman. This marriage was an unhappy one which constantly drove him to debt and caused scandals.

A collection of extraordinary tales appeared anonymously in the magazine Vademecum für lustige Leute (1781-1783), all of them attributed to the Baron, though several can be traced to much earlier sources.

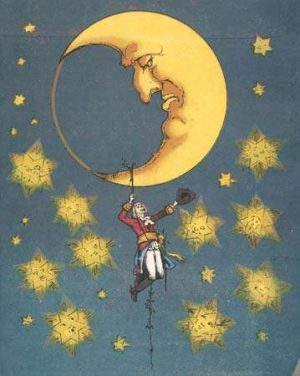

The baron recovering his silver casket, which had bounced up to the Moon, illustration from a 19th-century edition of The Adventures of Baron Munchausen by Rudolf Erich Raspe.

© Photos.com/Thinkstock

The man who created the Münchhausen myth was a family friend, a penniless scholar and librarian professor from Kassel, Rudolf Erich Raspe (1737-1794), who had had to flee England because of thefts. Raspe used the earlier stories as basic material, extended it, translated it into English, and published it anonymously in a small volume in London in 1785: Baron Munchhausens Narrative of His Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia. The book was a great success and the second edition was translated into German in 1786, in 1798 further extended with eight stories by the poet Gottfried August Bürger (1747-1894) and soon became a truly popular book.

The book became such a sensation that a year later, a German translation of Raspe’s anonymous book was published in Germany under the title the “Marvelous Travels on Water and Land: The Campaigns and Comical Adventures of the Baron of Münchhausen as commonly told over a bottle of wine at a table of friends”. The German version was even further expanded and exaggerated. Münchausen felt his honor wounded and reputation at stake. He attempted to take the translator, Godfried Bürger, to trial. However, the case was thrown out, as the judge stated that Burger had merely translated the work of an unknown author in England, and therefore was not at fault for any damage to Münchausen’s reputation. The trial never advanced beyond this point.

From that time on, the Baron knew no rest: he had been ridiculed and accused of lying, and had to hire servants to chase away gawkers from his estate with sticks, curious fans hoping to get a glimpse of the ‘King of Lies’.

It has been reported that the Baron suffered greatly from his new reputation of being insane, dying alone and childless in his home town of Bodenwerder. His stories leave a legacy of the tale of a man trying to regain his dignity from the world around him, and at the same time they inspire future generations of imagination with their impossibility, wit, and magic.