Germany’s leadership had hoped for a limited war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. But because Russian forces had been mobilized in support of Serbia, the German leadership made the decision to support its ally. The Schlieffen Plan, based on the assumption that Germany would face a two-front war because of a French-Russian alliance, required a rapid invasion through neutral Belgium to ensure the quick defeat of France. Once the western front was secure, the bulk of German forces could attack and defeat Russia, which would not yet be completely ready for war because it would mobilize its gigantic forces slowly.

Germany’s leadership had hoped for a limited war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. But because Russian forces had been mobilized in support of Serbia, the German leadership made the decision to support its ally. The Schlieffen Plan, based on the assumption that Germany would face a two-front war because of a French-Russian alliance, required a rapid invasion through neutral Belgium to ensure the quick defeat of France. Once the western front was secure, the bulk of German forces could attack and defeat Russia, which would not yet be completely ready for war because it would mobilize its gigantic forces slowly.

Despite initial successes, Germany’s strategy failed, and its troops became tied down in trench warfare in France. For the next four years, there would be little progress in the west, where advances were usually measured in meters rather than in kilometers. Under the command of Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff, the army scored a number of significant victories against Russia. But it was only in early 1918 that Russia was defeated. Even after this victory in the east, however, Germany remained mired in a long war for which it had not prepared.

Germany’s war aims were annexationist in nature and foresaw an enlarged Germany, with Belgium and Poland as vassal states and with colonies in Africa. In its first years, there was widespread support for the war. Even the SPD supported it, considering it a defensive effort and voting in favor of war credits. By 1916, however, opposition to the war had mounted within the general population, which had to endure many hardships, including food shortages. A growing number of Reichstag deputies came to demand a peace without annexations. Frustrated in its quest for peace, in April 1917 a segment of the SPD broke with the party and formed the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany. In July the Reichstag passed a resolution calling for a peace without annexations. In its wake, Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg was forced to resign, and Hindenburg and Ludendorff came to exercise a control over Germany until late 1918 that amounted to a virtual military dictatorship.

Germany’s war aims were annexationist in nature and foresaw an enlarged Germany, with Belgium and Poland as vassal states and with colonies in Africa. In its first years, there was widespread support for the war. Even the SPD supported it, considering it a defensive effort and voting in favor of war credits. By 1916, however, opposition to the war had mounted within the general population, which had to endure many hardships, including food shortages. A growing number of Reichstag deputies came to demand a peace without annexations. Frustrated in its quest for peace, in April 1917 a segment of the SPD broke with the party and formed the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany. In July the Reichstag passed a resolution calling for a peace without annexations. In its wake, Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg was forced to resign, and Hindenburg and Ludendorff came to exercise a control over Germany until late 1918 that amounted to a virtual military dictatorship.

Military leaders refused a moderate peace because they were convinced until very late in the war that victory ultimately would be theirs. Another reason for their insistence on a settlement that fulfilled expansionist aims was that the government had not financed the war with higher taxes but with bonds. Taxes had been seen as unnecessary because it was expected that the government would redeem these bonds after the war with payments from Germany’s vanquished enemies. Thus, only an expansionist victory would keep the state solvent and save millions of German bondholders from financial ruin.

After the Bolshevik Revolution of November 1917, Russia and Germany began peace negotiations. In March 1918, the two countries signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The defeat of Russia enabled Germany to transfer troops from the eastern to the western front. Two large offensives in the west were met by an Allied counteroffensive that began in July. German troops were pressed back, and it became evident to many officers that Germany could not win the war. In September Ludendorff recommended that Germany sue for peace. In October extensive reforms democratized the Reichstag and gave Germany a constitutional monarchy. A coalition of progressive forces was formed, headed by SPD politician Friedrich Ebert. The military allowed the birth of a democratic parliament because it did not want to be held responsible for the inevitable armistice that would end the war on terms highly unfavorable to Germany. Instead, the civilian government that signed the truce was to take the blame for the nation’s defeat.

After the Bolshevik Revolution of November 1917, Russia and Germany began peace negotiations. In March 1918, the two countries signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The defeat of Russia enabled Germany to transfer troops from the eastern to the western front. Two large offensives in the west were met by an Allied counteroffensive that began in July. German troops were pressed back, and it became evident to many officers that Germany could not win the war. In September Ludendorff recommended that Germany sue for peace. In October extensive reforms democratized the Reichstag and gave Germany a constitutional monarchy. A coalition of progressive forces was formed, headed by SPD politician Friedrich Ebert. The military allowed the birth of a democratic parliament because it did not want to be held responsible for the inevitable armistice that would end the war on terms highly unfavorable to Germany. Instead, the civilian government that signed the truce was to take the blame for the nation’s defeat.

The political reforms of October were overshadowed by a popular uprising that began on November 3 when sailors in Kiel mutinied. They refused to go out on what they considered a suicide mission against British naval forces. The revolt grew quickly and within a week appeared to be burgeoning into a revolution that could well overthrow the established social order. On November 9, the Kaiser was forced to abdicate, and the SPD proclaimed a republic. A provisional government headed by Ebert promised elections for a national assembly to draft a new constitution. In an attempt to control the popular uprising, Ebert agreed to back the army if it would suppress the revolt. On November 11, the government signed the armistice that ended the war. Germany’s loses included about 1.6 million dead and more than 4 million wounded.

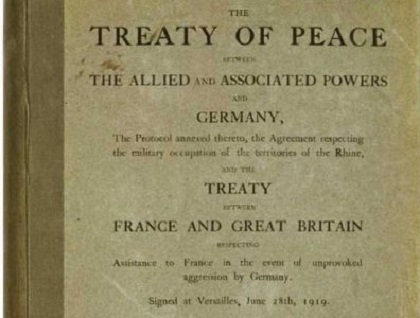

Signed in June 1919, the Treaty of Versailles limited Germany to an army of 100,000 soldiers. The treaty also stipulated that the Rhineland be demilitarized and occupied by the western Allies for fifteen years and that Germany surrender Alsace-Lorraine, northern Schleswig-Holstein, a portion of western Prussia that became known as the Polish Corridor because it gave Poland access to the Baltic, and all overseas colonies. Also, an Allied Reparations Commission was established and charged with setting the amount of war-damage payments that would be demanded of Germany. The treaty also included the “war guilt clause,” ascribing responsibility for World War I to Germany and Austria-Hungary.

Signed in June 1919, the Treaty of Versailles limited Germany to an army of 100,000 soldiers. The treaty also stipulated that the Rhineland be demilitarized and occupied by the western Allies for fifteen years and that Germany surrender Alsace-Lorraine, northern Schleswig-Holstein, a portion of western Prussia that became known as the Polish Corridor because it gave Poland access to the Baltic, and all overseas colonies. Also, an Allied Reparations Commission was established and charged with setting the amount of war-damage payments that would be demanded of Germany. The treaty also included the “war guilt clause,” ascribing responsibility for World War I to Germany and Austria-Hungary.

Related articles:

Imperial Germany – the Second Reich

Political Parties in Imperial Germany

The Economy and Population Growth in Germany

The Tariff Agreement of 1879 in Germany and Its Social Consequences

Bismarck’s Foreign Policy

Foreign Policy in the Wilhelmine Era