Following the death of Henry V (r. 1106-25), the last of the Salian kings, the dukes refused to elect his nephew because they feared that he might restore royal power. Instead, they elected a noble connected to the Saxon noble family Welf (often written as Guelf). This choice inflamed the Hohenstaufen family of Swabia, which also had a claim to the throne. Although a Hohenstaufen became king in 1138, the dynastic feud with the Welfs continued. The feud became international in nature when the Welfs sided with the papacy and its allies, most notably the cities of northern Italy, against the imperial ambitions of the Hohenstaufen Dynasty.

Following the death of Henry V (r. 1106-25), the last of the Salian kings, the dukes refused to elect his nephew because they feared that he might restore royal power. Instead, they elected a noble connected to the Saxon noble family Welf (often written as Guelf). This choice inflamed the Hohenstaufen family of Swabia, which also had a claim to the throne. Although a Hohenstaufen became king in 1138, the dynastic feud with the Welfs continued. The feud became international in nature when the Welfs sided with the papacy and its allies, most notably the cities of northern Italy, against the imperial ambitions of the Hohenstaufen Dynasty.

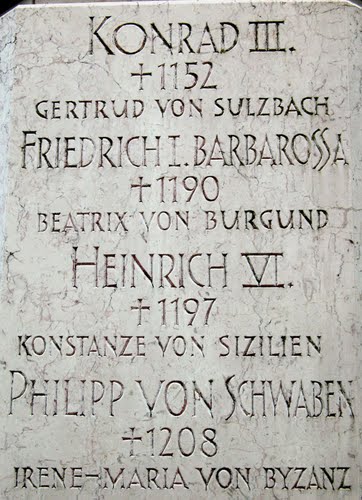

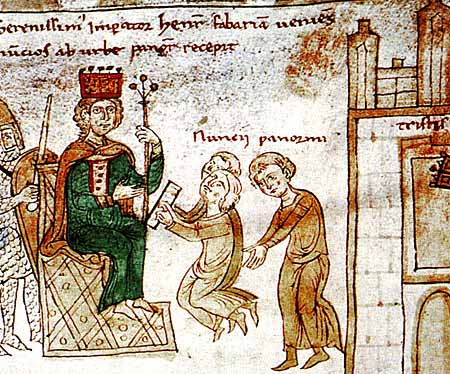

The second of the Hohenstaufen rulers, Frederick I (r. 1152-90), also known as Frederick Barbarossa because of his red beard, struggled throughout his reign to restore the power and prestige of the German monarchy, but he had little success. Because the German dukes had grown stronger both during and after the Investiture Contest and because royal access to the resources of the church in Germany was much reduced, Frederick was forced to go to Italy to find the finances needed to restore the king’s power in Germany. He was soon crowned emperor in Italy, but decades of warfare on the peninsula yielded scant results. The papacy and the prosperous city-states of northern Italy were traditional enemies, but the fear of imperial domination caused them to join ranks to fight Frederick. Under the skilled leadership of Pope Alexander III, the alliance suffered many defeats but ultimately was able to deny the emperor a complete victory in Italy. Frederick returned to Germany old and embittered. He had vanquished one notable opponent and member of the Welf family, Saxony’s Henry the Lion, but his hopes of restoring the power and prestige of his family and the monarchy seemed unlikely to be met by the end of his life.

During Frederick’s long stays in Italy, the German princes became stronger and began a successful colonization of Slavic lands. Offers of reduced taxes and manorial duties enticed many Germans to settle in the east as the area’s original inhabitants were killed or driven away. Because of this colonization, the empire increased in size and came to include Pomerania, Silesia, Bohemia, and Moravia. A quickening economic life in Germany increased the number of towns and gave them greater importance. It was also during this period that castles and courts replaced monasteries as centers of culture. Growing out of this courtly culture, German medieval literature reached its peak in lyrical love poetry, the Minnesang, and in narrative epic poems such as Tristan, Parsifal, and the Nibelungenlied.

Frederick died in 1190 while on a crusade and was succeeded by his son, Henry VI (r. 1190-97). Elected king even before his father’s death, Henry went to Rome to be crowned emperor. A death in his wife’s family gave him possession of Sicily, a source of vast wealth. Henry failed to make royal and imperial succession hereditary, but in 1196 he succeeded in gaining a pledge that his infant son Frederick would receive the German crown. Faced with difficulties in Italy and confident that he would realize his wishes in Germany at a later date, Henry returned to the south, where it appeared he might unify the peninsula under the Hohenstaufen name. After a series of military victories, however, he died of natural causes in Sicily in 1197.

Frederick died in 1190 while on a crusade and was succeeded by his son, Henry VI (r. 1190-97). Elected king even before his father’s death, Henry went to Rome to be crowned emperor. A death in his wife’s family gave him possession of Sicily, a source of vast wealth. Henry failed to make royal and imperial succession hereditary, but in 1196 he succeeded in gaining a pledge that his infant son Frederick would receive the German crown. Faced with difficulties in Italy and confident that he would realize his wishes in Germany at a later date, Henry returned to the south, where it appeared he might unify the peninsula under the Hohenstaufen name. After a series of military victories, however, he died of natural causes in Sicily in 1197.

Because the election of the three-year-old Frederick to be German king appeared likely to make orderly rule difficult, the boy’s uncle, Philip, was chosen to serve in his place. Other factions elected a Welf candidate, Otto IV, as counterking, and a long civil war began. Philip was murdered by Otto IV in 1208. Otto IV in turn was killed by the French at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214. Frederick returned to Germany in 1212 from Sicily, where he had grown up, and became king in 1215. As Frederick II (r. 1215-50), he spent little time in Germany because his main concerns lay in Italy. Frederick made significant concessions to the German nobles, such as those put forth in an imperial statute of 1232, which made princes virtually independent rulers within their territories. The clergy also became more powerful. Although Frederick was one of the most energetic, imaginative, and capable rulers of the Middle Ages, he did nothing to draw the disparate forces in Germany together. His legacy was thus that local rulers had more authority after his reign than before it.

By the time of Frederick’s death in 1250, there was little centralized power in Germany. The Great Interregnum (1256-73), a period of anarchy in which there was no emperor and German princes vied for individual advantage, followed the death of Frederick’s son Conrad IV in 1254. In this short period, the German nobility managed to strip many powers away from the already diminished monarchy. Rather than establish sovereign states, however, many nobles tended to look after their families. Their many heirs created more and smaller estates. A largely free class of officials also formed, many of whom eventually acquired hereditary rights to administrative and legal offices. These trends compounded political fragmentation within Germany.

Despite the political chaos of the Hohenstaufen period, the population grew from an estimated 8 million in 1200 to about 14 million in 1300, and the number of towns increased tenfold. The most heavily urbanized areas of Germany were located in the south and the west. Towns often developed a degree of independence, but many were subordinate to local rulers or the emperor. Colonization of the east also continued in the thirteenth century, most notably through the efforts of the Knights of the Teutonic Order, a society of soldier-monks. German merchants also began trading extensively on the Baltic.

Related articles:

– The Merovingian Dynasty, ca. 500-751

– The Carolingian Dynasty, 752-911

– The Saxon Dynasty, 919-1024

– The Salian Dynasty, 1024-1125

– The Empire under the Early Habsburgs