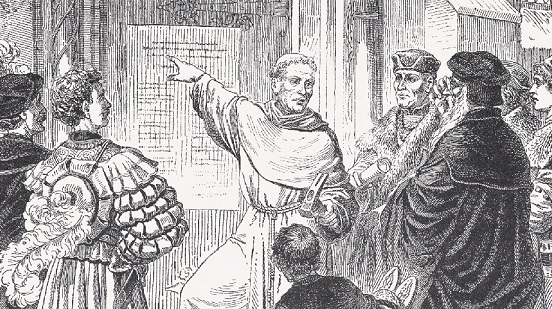

It’s October 31, 1517. A monk named Martin Luther, hammer in hand, walks to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. In a single act, he nails a list of 95 arguments – against the abuse of indulgences and Church corruption – to the door. He’s not seeking to start a revolution. But within months, Germany is ablaze with debate.

Luther’s 95 Theses lit the fuse on the Protestant Reformation, a movement that would split Christianity, challenge monarchs, inspire wars, and birth modern concepts of freedom, conscience, and nationhood. Let’s step into the world of Luther – and explore why one document changed everything.

The Man Behind the Hammer

Martin Luther was born in 1483 in Eisleben, Saxony. Originally studying law, he abandoned that path after a near-death experience in a thunderstorm. He became an Augustinian monk, later earning a doctorate in theology and becoming a professor at the University of Wittenberg.

Luther was deeply spiritual – and deeply troubled. He feared damnation and questioned whether the Church’s sacraments could truly offer salvation. Through study, especially of St. Paul’s letters, he reached a turning point: salvation came not by works or money, but by faith alone (sola fide).

Indulgences and Corruption

The 95 Theses were Luther’s response to a very specific practice: the sale of indulgences. These were payments made to the Church in exchange for reduced punishment in purgatory. In Luther’s view, this practice was not only unscriptural – it was spiritually damaging.

In 1517, a Dominican friar named Johann Tetzel began aggressively selling indulgences near Wittenberg. His famous jingle: “As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs.” Luther was appalled.

His theses were not originally intended as rebellion. They were a scholarly invitation to debate – written in Latin, following academic custom. But they spread fast. Translated into German, printed on Gutenberg’s new press, they traveled like wildfire across the empire.

The Core of the 95 Theses

While many of the theses are technical, Luther’s main arguments included:

- The pope has no power over purgatory.

- Forgiveness cannot be bought.

- True repentance requires inner change – not financial transaction.

- The Church should focus on preaching the Gospel, not raising money.

Luther questioned the entire system of spiritual economy that had dominated medieval Christianity.

Rome Reacts

At first, Church officials dismissed Luther as a nuisance. But as his following grew, Rome demanded he recant. In 1520, Luther responded with three radical works:

- “Address to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation”

- “On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church”

- “On the Freedom of a Christian”

In them, he:

- Rejected papal authority

- Called for reform of the priesthood

- Argued that every believer was a priest in their own right

In 1521, he was excommunicated and summoned to the Diet of Worms by Emperor Charles V. There, Luther made his legendary stand:

“Unless I am convinced by Scripture and plain reason… I cannot and will not recant. Here I stand. I can do no other.”

Luther in Hiding and the German Bible

After Worms, Luther was declared an outlaw. He was secretly sheltered by Frederick the Wise in Wartburg Castle, where he began translating the New Testament into German.

This translation:

- Made the Bible accessible to common people

- Standardized German language

- Undermined clerical control of scripture

Luther’s version was both elegant and readable, helping spread vernacular literacy and giving Germans a shared linguistic identity.

Social and Political Turmoil

The Reformation wasn’t just theological – it was deeply political:

- Many German princes saw Luther’s movement as a way to gain independence from Rome.

- Printing presses and pamphlet wars created a new public sphere of opinion.

- Peasants interpreted Luther’s teachings as calls for social justice, culminating in the German Peasants’ War (1524–1525).

Though sympathetic at first, Luther ultimately sided with the nobility. His rejection of the peasants’ violence disappointed many – and exposed tensions between religious ideals and social realities.

The Birth of Protestantism

By the late 1520s, Luther’s ideas had inspired the formation of:

- Lutheran churches in German territories

- Reformed movements in Switzerland and beyond

- New doctrines like sola scriptura (scripture alone) and sola gratia (grace alone)

The Protestant Reformation fractured the Church but also democratized religion – putting spiritual authority into the hands of individuals and communities.

Legacy and Impact on Germany

Luther died in 1546, but his influence endured:

- Germany became divided between Catholic and Protestant states

- Wars of religion, culminating in the Thirty Years’ War, devastated Central Europe

- Literacy and education spread through Protestant regions

- New ideas of individual conscience, religious tolerance, and national identity emerged

Today, Luther is remembered both as a reformer and a controversial figure—praised for his courage, criticized for his later writings against Jews and radicals. But few doubt his impact.

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses marked a turning point in German – and world – history. What began as an academic protest became a spiritual revolution, a media event, and a political upheaval all at once. It cracked open centuries of religious authority and sparked a wave of transformation that continues to shape belief, identity, and freedom.

Related Topics:

Reformation and Early Modern Period – Explore the major transformations in German history from the 16th to early 19th centuries, including religious upheaval, political change, and cultural milestones.

The German Peasants’ War (1524–1525) – A major uprising of peasants and lower classes inspired by Reformation ideals, this war revealed deep social tensions in early modern Germany.

The Thirty Years’ War and Its Impact on Germany – This devastating conflict reshaped Central Europe, leading to massive depopulation, destruction, and long-term political fragmentation in the German lands.

The Peace of Augsburg – Discover the Peace of Augsburg, its role in shaping Germany’s religious landscape, and how it laid the groundwork for centuries of conflict and compromise.

The Peace of Westphalia (1648) – The treaty that ended the Thirty Years’ War established new political boundaries and is considered a foundation of modern international diplomacy.

Rise of Brandenburg-Prussia – Follow the emergence of Brandenburg-Prussia as a rising power in northern Germany, laying the groundwork for future German unification.

The Enlightenment in the German States – Learn how German philosophers, writers, and reformers contributed to the broader European Enlightenment with ideas on reason, science, and governance.

German Scientific and Cultural Achievements (18th Century) – Explore the flourishing of music, philosophy, and science in 18th-century Germany, from Bach and Goethe to Kant and Humboldt.

Frederick the Great of Prussia – Examine the reign of Frederick II, a military strategist and Enlightened monarch who modernized Prussia and expanded its influence.

The Napoleonic Wars and the Confederation of the Rhine – Discover how Napoleon’s reshaping of German territories led to the end of the Holy Roman Empire and the formation of a French-aligned confederation.

The Congress of Vienna and the German Confederation – Understand how European powers redrew the map after Napoleon’s defeat, establishing the German Confederation as a loose alliance of states.