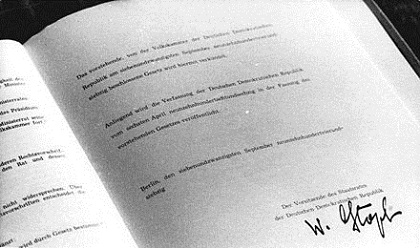

Although the GDR had finally achieved its goal of international recognition with the signing of the Basic Treaty in December 1972, renewed concerns about the stability and identity of the GDR as a second German state drove the SED Politburo toward a policy of reaffirming the socialist nature of the state. As early as 1971, Honecker had launched a campaign to foster a socialist identity among East Germans and to counter West German emphasis on the historical unity of the German nation. In 1974 the GDR constitution was even amended to increase a sense of separate development. All references in the document to the “German nation” and to German national heritage were deleted.

Although the GDR had finally achieved its goal of international recognition with the signing of the Basic Treaty in December 1972, renewed concerns about the stability and identity of the GDR as a second German state drove the SED Politburo toward a policy of reaffirming the socialist nature of the state. As early as 1971, Honecker had launched a campaign to foster a socialist identity among East Germans and to counter West German emphasis on the historical unity of the German nation. In 1974 the GDR constitution was even amended to increase a sense of separate development. All references in the document to the “German nation” and to German national heritage were deleted.

The SED had long revised German history to make it conform to socialist purposes. Symbols of Prussian heritage in Berlin, such as the equestrian statue of Prussian king Frederick the Great, had been removed. And in 1950, Ulbricht had ordered the 500-year-old palace of the Hohenzollern Dynasty demolished because it was a symbol of “feudal repression.”

Just as the SED was striving to develop a separate GDR consciousness and loyalty, however, the new access to Western media, arranged by the CSCE process and formalized in the Helsinki Accords of 1975, was engendering a growing enthusiasm among East Germans for West Germany’s Ostpolitik. Honecker sought to counter this development by devising a new formula: “citizenship, GDR; nationality, German.” After the SED’s Ninth Party Congress in May 1976, Honecker went one step further: figures of Prussian history, such as the reformers Karl vom Stein, Karl August von Hardenberg, Gerhard von Scharnhorst, and the founder of Berlin University, Wilhelm von Humboldt, were rehabilitated and claimed as historical ancestors of the GDR. Frederick the Great and Otto von Bismarck were also restored to prominence. Even Martin Luther was judged a worthy historical figure who needed to be understood within the context of his times.

These concessions did not alter the regime’s harsh policy toward dissidents, however. Primary targets were artists and writers who advocated reforms and democratization, including Wolf Biermann, a poet-singer popular among East German youth who was expelled from the GDR in 1976. A wave of persecution of other dissident intellectuals followed. Some were imprisoned; others were deported to West Germany. Nonetheless, political statements by East German intellectuals, some going so far as to advocate reunification, continued to appear anonymously in the West German press.

Related articles:

The Honecker Era, 1971-89

The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

Relations Between the Two Germanys

The Peace Movement and Internal Resistance in GDR

The Last Days of East Germany