The roots of German history begin long before the emergence of a unified German state. The earliest ancestors of the Germanic peoples lived during prehistoric times, migrating and evolving into the tribal cultures that would one day challenge Rome and shape medieval Europe. Understanding their origins offers deep insight into how geography, culture, and contact with other civilizations influenced what would become Germany.

The Prehistoric Foundations

The story begins in northern Europe during the Nordic Bronze Age (circa 1700–500 BCE). Societies across present-day Denmark, southern Sweden, and northern Germany thrived in coastal and forested environments. Archaeological evidence shows these early groups built longhouses, practiced agriculture, crafted bronze tools, and traded with Celtic and Baltic neighbors.

By around 500 BCE, a cultural shift known as the Jastorf culture emerged in northern Germany. This society, often associated with early Germanic identity, marked a clear departure from previous Bronze Age customs. Iron replaced bronze, cremation replaced inhumation, and distinct burial practices and material culture appeared.

Language and Identity

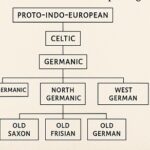

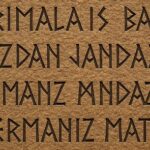

Linguistically, these people spoke an early form of Proto-Germanic, a branch of the larger Indo-European language family. Over time, this language split into the East, North, and West Germanic dialects that gave rise to Gothic, Old Norse, Old High German, and other languages.

Though we cannot speak of a single “Germanic identity” in this era, shared language, material culture, and oral tradition began to unify various tribes under a common umbrella—setting the foundation for cultural distinction from neighboring Celts and Slavs.

Germanic Migration and Expansion

Around the 1st century BCE, the Germanic tribes began a southward migration, driven by population growth, resource pressures, and climate change. They expanded into Central Europe, where they encountered the Roman Empire.

Tribes such as the Suebi, Cherusci, and Marcomanni settled along the Rhine and Danube frontiers. The Roman historian Tacitus, in his work Germania (circa 98 CE), provided one of the earliest and most detailed outsider accounts of these people—depicting them as fierce, independent, and deeply rooted in tribal loyalty and tradition.

“They choose their kings for their noble birth, their generals for their valor.” — Tacitus, Germania

This period saw the beginnings of cultural differentiation, as each tribe developed unique political structures, warrior codes, and interactions with Rome and neighboring peoples.

Social and Political Structure

The Germanic tribes were organized into clans and kin groups, with leadership based on family lineage, charisma, and martial success. Tribal assemblies (things) made key decisions, a tradition that influenced later German legal and parliamentary culture.

Their societies were deeply stratified: warriors and chieftains held power, while freemen worked land or fought, and slaves (often war captives) performed labor. Women played important roles in managing households and preserving oral traditions.

Religion during this era was animistic and polytheistic. Worship centered on gods of war, fertility, and nature—early forms of Odin, Thor, and Freya appeared. Sacred groves and rivers were revered, and offerings or sacrifices were common ritual acts.

Technological and Cultural Markers

- Agriculture: Grain cultivation and livestock herding

- Craftsmanship: Iron tools, pottery, textiles, and jewelry

- Housing: Timber longhouses built for entire extended families

- Burial Rites: Cremation urnfields and later tumulus (burial mounds)

These practices reflected both innovation and long-standing ties to land and ancestry.

Contact with the Celts and Romans

Germanic tribes were never isolated. They interacted frequently with Celtic neighbors to the west and Roman forces to the south. Trade routes brought Roman goods—glassware, coins, and weapons—into Germanic hands, influencing local economies and elite prestige.

However, tension escalated. As Rome pushed its frontier into Gaul and the Rhineland, the Germanic peoples increasingly found themselves resisting imperial control. This friction would culminate in landmark events like the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (9 CE)—a defining moment in German-Roman relations explored in our article on Arminius and the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest.

Legacy and Importance

By the 3rd century CE, the identity of the Germanic peoples was fully formed. They had established themselves as formidable military powers, dynamic traders, and custodians of a rich cultural tradition.

From these roots emerged the tribes who would later become the Goths, Franks, Saxons, and Lombards—each leaving their own imprint on the lands of Europe. Their legacy is evident in the languages, folklore, and political structures of modern Germany.

The origins of the Germanic peoples lie in a deep prehistoric past, one shaped by climate, culture, and constant movement. Though they would not unify into a single nation for many centuries, their early development laid the foundations for everything that followed in German history.

For more on how these tribes transformed under Roman influence, see Germanic Tribes and Roman Confrontation. You can also explore their evolution into kingdoms in The Rise of the Franks and Charlemagne and the Carolingian Empire.