Participants at the Potsdam Conference had agreed that the foreign ministers of the four victorious powers should meet to implement and monitor the conference’s decisions about postwar Europe. During their fifth meeting, held in London in late 1947, prospects for concluding a peace treaty with Germany were examined. Following lengthy discussions on the question of reparations, the conference ended without any concrete decisions.

Participants at the Potsdam Conference had agreed that the foreign ministers of the four victorious powers should meet to implement and monitor the conference’s decisions about postwar Europe. During their fifth meeting, held in London in late 1947, prospects for concluding a peace treaty with Germany were examined. Following lengthy discussions on the question of reparations, the conference ended without any concrete decisions.

The tense atmosphere during the talks and the uncooperative attitude of the Soviet participants convinced the Western Allies of the necessity of a common political order for the three Western zones. At the request of France, the Western Allies were joined by Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg at the subsequent Six Power Conference in London, which met in two sessions in the spring of 1948.

The recommendations of this conference were contained in the so-called Frankfurt Documents, which the military governors of the Western zones issued to German political leaders, the minister presidents of the Western Länder on July 1, 1948. The documents called for convening a national convention to draft a constitution for a German state formed from the Western occupation zones. The documents also contained the announcement of an Occupation Statute, which was to define the position of the occupation powers vis-à-vis the new state.

The minister presidents initially objected to the creation of a separate political entity in the west because they feared such an entity would cement the division of Germany. Gradually, however, it became apparent that the division of the country was already a fact. To emphasize the provisional nature of the document they were to draft, the minister presidents rejected the designation “constitution” and agreed on the term “Basic Law” (Grundgesetz). Final approval of the Basic Law, whose articles were to be worked out by a parliamentary council, was to be given by a vote of the Land diets, and not by referendum, as suggested in the Frankfurt Documents. Once the Allies had accepted these and other modifications, a constitutional convention was called to draft the Basic Law.

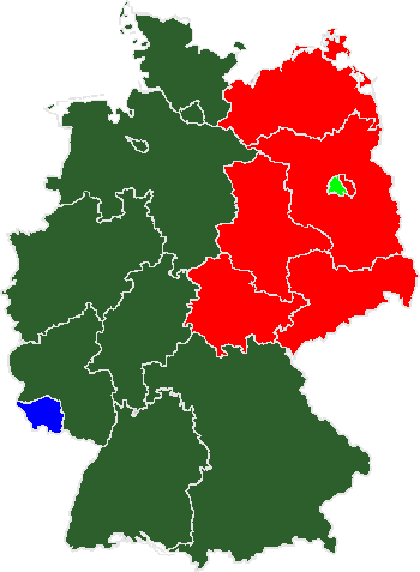

The convention met in August 1948 in Bavaria at Herrenchiemsee. After completing its work, the Parliamentary Council, consisting of sixty-five delegates from the respective Land diets and chaired by leading CDU politician Konrad Adenauer, met in Bonn in the fall of 1948 to work out the final details of the document. After months of debate, the final text of the Basic Law was approved by a vote of fifty-three to twelve on May 8, 1949. The new law was ratified by all Land diets, with the exception of the Bavarian parliament, which objected to the emphasis on a strong central authority for the new state. After approval by the Western military governors, the Basic Law was promulgated on May 23, 1949. A new state, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, or West Germany), had come into existence.

The members of the Parliamentary Council that fashioned the articles of the Basic Law were fully aware of the constitutional deficiencies that had brought down the Weimar Republic. They sought, therefore, to approve a law that would make it impossible to circumvent democratic procedures, as had occurred in the past. The powers of the lower house, the Bundestag, and the federal chancellor were enhanced considerably at the expense of the federal president, who was reduced to a figurehead. Prime consideration was given to the basic rights and the dignity of the individual. The significance of the Länder was enhanced by their direct influence on legislation through representation in the upper house, the Bundesrat. The Basic Law also safeguarded parliamentary government by protecting the federal chancellor from being forced from power through a simple vote of no-confidence. Instead, a constructive vote of no-confidence was required, that is, the vote’s sponsors were required to name a replacement able to win the necessary parliamentary support. The Basic Law also supported the principle of a free market, as well as a strong social security system. In summary, the new Basic Law showed striking similarities to the constitution of the United States. To underscore its provisional character, Article 146 of the Basic Law stated that the document was to be replaced as soon as all German people were free to determine their own future.

According to the Basic Law, the Federal Constitutional Court could ban a political party that aimed at obstructing or abolishing the system of democracy. The activities of a number of openly antidemocratic parties during the Weimar Republic had inspired the authors of the Basic Law to include this strong provision. In 1952 the Socialist Reich Party (Sozialistische Reichspartei–SRP), a successor to the NSDAP, became the first party to be banned. The SRP had maintained that the Third Reich still existed legally, and it had denied the legitimacy of the FRG as a state. A few years later, the KPD was also suspended. Although the KPD was at first represented in all Land parliaments, it gradually lost support. After 1951 the leadership of the KPD began to pursue an openly revolutionary course and advocated the overthrow of the government. After five years of deliberations, the Federal Constitutional Court declared the KPD unconstitutional.

Related articles:

Postwar Occupation and Division

The Nuremberg Trials and Denazification

Postwar Political Parties in Germany

The Creation of the Bizone

The Birth of the German Democratic Republic