By the 14th and 15th centuries, the Holy Roman Empire was no longer the centralized dream of Charlemagne. Instead, it had evolved into a sprawling collection of kingdoms, duchies, bishoprics, free cities, and principalities—each fiercely guarding its independence while still pledging some form of loyalty to the emperor.

This period, often dismissed as politically fractured, was in fact an age of transformation. The Late Middle Ages saw the empire survive plague, papal schism, war, and economic turmoil, while laying the groundwork for cultural and institutional innovations that would echo well into the modern era.

Let’s dive into how the Holy Roman Empire navigated the turbulence of the Late Middle Ages—and how it redefined what it meant to rule a German realm.

A Decentralized Patchwork of Power

By the 1300s, the Holy Roman Empire had long abandoned the ideal of a unified, top-down monarchy. Power was increasingly dispersed:

- Electors and princes ruled their territories like sovereign monarchs.

- Imperial free cities governed themselves independently.

- The Golden Bull of 1356, issued by Emperor Charles IV, codified this decentralization, granting hereditary rights to seven prince-electors and solidifying their political autonomy.

The empire became less a nation-state and more a federated realm, in which loyalty to the emperor was conditional and practical rather than deeply binding. It was, as Voltaire later quipped, “neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire”—but it worked.

The Emperors: Balancing Power and Prestige

Emperors like Charles IV, Sigismund, and later Frederick III had to rule more by consensus than command:

- They relied on imperial diets (Reichstage) to pass laws and approve taxes.

- Much of their authority stemmed from their dynastic houses (Luxembourg, Habsburg, etc.) rather than imperial institutions.

- They traveled constantly, reinforcing loyalty and resolving disputes—a style known as the itinerant kingship.

Charles IV in particular was a skilled diplomat. He established Prague as an imperial capital, founded the University of Prague in 1348, and crafted a vision of a culturally rich, multi-ethnic empire centered on Bohemia.

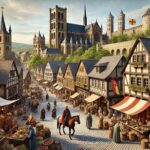

Rise of the Cities and Urban Power

Cities grew rapidly in wealth and influence during this period:

- Towns like Nuremberg, Augsburg, and Cologne became hubs of trade, craft production, and legal autonomy.

- Free imperial cities answered directly to the emperor and often operated like mini-republics.

- Cities joined defensive leagues such as the Swabian League to counterbalance noble and princely power.

Urban elites—merchants, guild masters, and lawyers—rose in status, forming an early bourgeois class that challenged the social dominance of nobility and clergy.

Trade routes tied German cities into wider European markets:

- The Hanseatic League connected the North Sea and Baltic ports.

- Inland cities profited from silver mining, textile production, and banking innovations.

Cultural Renaissance and Intellectual Growth

Despite war and plague, the Late Middle Ages in Germany was also a time of cultural flowering:

- Cathedrals like Cologne and Ulm rose skyward in breathtaking Gothic style.

- Universities—such as Heidelberg (1386) and Leipzig (1409)—trained clerics, lawyers, and administrators.

- Mystical movements, led by figures like Meister Eckhart, stressed direct experience of God.

- Minnesingers and urban poets preserved and evolved German literary traditions.

Manuscript production boomed, and educated clergy began to question not only church abuses, but also social injustice—a key precursor to later reform movements.

Crisis and Transformation

This was also a time of great uncertainty:

- The Black Death (1347–1352) killed as much as half the population in some areas.

- The Western Schism (1378–1417) split papal allegiance and confused political loyalty.

- Peasant revolts and urban unrest erupted in response to economic hardship and lordly exploitation.

Yet the empire adapted. New forms of governance, diplomacy, and representation evolved. Regional rulers developed sophisticated courts, and towns adopted written charters and legal codes.

The Habsburgs and the Turn Toward Stability

By the end of the 15th century, the Habsburgs were rising. With the election of Frederick III in 1440 and later Maximilian I, they began a process of dynastic consolidation:

- Marriages and treaties brought vast territories under Habsburg control.

- Imperial reforms in the 1490s created the Imperial Circle system, the Imperial Chamber Court, and more structured administration.

- Though far from centralized, the empire entered a phase of relative order.

Maximilian’s reign (r. 1493–1519) is often seen as the bridge between medieval empire and early modern statecraft.

Legacy of the Late Medieval Empire

Despite its complexity—and frequent dysfunction—the empire in this period had profound achievements:

- It preserved regional identities while offering an overarching framework of legitimacy.

- It nurtured German cities as cultural and economic powerhouses.

- It developed the political traditions of elective monarchy, legal pluralism, and representative assemblies.

In many ways, its flexibility became its strength. While France and England moved toward absolutism, Germany explored another path: negotiated sovereignty and local autonomy within a shared imperial tradition.

The Holy Roman Empire in the Late Middle Ages wasn’t a single kingdom. It was a living mosaic—of power and piety, of autonomy and allegiance. Its legacy shaped not only Germany’s borders and institutions but also its enduring sense of regional diversity and political compromise.

To explore what came next, dive into The Reformation and Religious Conflicts in Germany, or look back at the roots of imperial power in The Golden Bull of 1356 and Medieval German Feudal Society.

Otto I and the Birth of the Holy Roman Empire – Explore how Otto I’s coronation in 962 marked the formal beginning of the Holy Roman Empire, establishing a powerful political and religious legacy in medieval Germany.

The Middle Ages in German History – An overview of the political, cultural, and religious transformations that shaped Germany from the fall of the Carolingian Empire to the dawn of the Reformation, including the rise of the Holy Roman Empire and medieval society.

Medieval German Feudal Society – Learn how landholding, loyalty, and class defined the social structure of medieval Germany, shaping both everyday life and royal authority.

The Hanseatic League – Discover the rise of this powerful trade alliance of northern German cities that dominated commerce across the Baltic and North Seas during the late Middle Ages.

German Castles and Knightly Culture – Dive into the architectural and chivalric world of medieval Germany, where fortified castles and knightly ideals shaped warfare, literature, and noble identity.

The Investiture Controversy – A pivotal power struggle between church and state, this conflict reshaped the relationship between emperors and popes across the German medieval landscape.

The Black Death in Germany – Trace the devastating impact of the 14th-century plague on German towns and villages, altering demographics, labor systems, and religious life.

Peasant Revolts in the Middle Ages – Examine the causes and consequences of peasant uprisings in medieval Germany, including their role in challenging feudal oppression and economic hardship.

The Teutonic Knights and Eastern Expansion – Follow the military and missionary campaigns of the Teutonic Order as they expanded Germanic influence eastward into pagan territories.

German Medieval Universities – Explore the intellectual revival of the High Middle Ages, as cathedral schools and universities flourished in German cities, preserving classical knowledge and fostering new ideas.

The Golden Bull of 1356 – Understand the constitutional landmark that formalized the election of German kings, shaping imperial governance in the Holy Roman Empire for centuries.