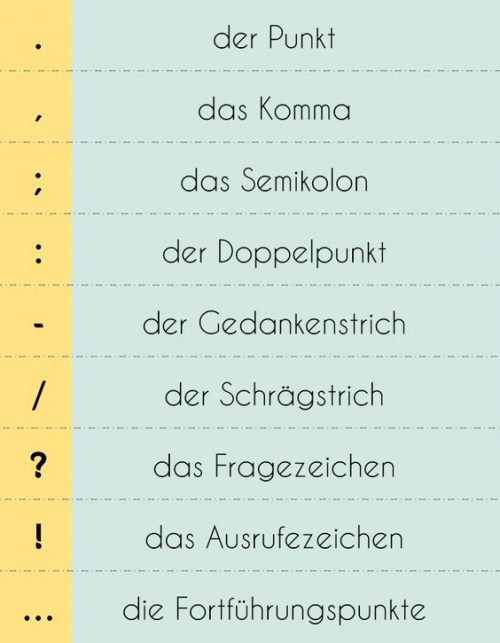

An essential part of learning to write in German is learning how to properly use German punctuation – a system of marks or signs that are placed in a text to clarify meaning and separate structural units. Luckily, German punctuation is similar to English punctuation in many respects.

An essential part of learning to write in German is learning how to properly use German punctuation – a system of marks or signs that are placed in a text to clarify meaning and separate structural units. Luckily, German punctuation is similar to English punctuation in many respects.

However, four of these German punctuation marks – quotation marks, the apostrophe, the comma and the dash – differ from their English counterparts in terms of how they are used.

1. Anführungszeichen (Quotation Marks)

A. German uses two types of quotation marks in printing. “Chevron” style marks (French “guillemets”) are often used in modern books:

Er sagte: «Wir gehen am Dienstag.»

or

Er sagte: »Wir gehen am Dienstag.«

In writing, in newspapers, and in many printed documents German also uses quotation marks that are similar to English except that the opening quotation mark is below rather than above: Er sagte: „Wir gehen am Dienstag.” (Note that unlike English, German introduces a direct quotation with a colon rather than a comma.)

In email, on the Web, and in hand-written correspondence, German-speakers today often use normal international quotation marks (“ ”) or even single quote marks (‘ ’).

B. When ending a quotation with “he said” or “she asked,” German follows British-English style punctuation, placing the comma outside of the quotation mark rather than inside, as in American English: „Das war damals in Berlin”, sagte Paul.

„Kommst du mit?”, fragte Luisa.

C. German uses quotation marks in some instances where English would use italics (Kursiv). Quotation marks are used in English for the titles of poems, articles, short stories, songs and TV shows. German expands this to the titles of books, novels, films, dramatic works and the names of newspapers or magazines, which would be italicized (or underlined in writing) in English:

„Fiesta” („The Sun Also Rises”) ist ein Roman von Ernest Hemingway. — Ich las den Artikel „Die Arbeitslosigkeit in Deutschland” in der „Berliner Morgenpost”.

D. German uses single quotation marks (halbe Anführungszeichen) for a quotation within a quotation in the same way English does:

„Das ist eine Zeile aus Goethes ,Erlkönig’”, sagte er.

Also see item 4B below for more about quotations in German.

2. Apostroph (Apostrophe)

A. German generally does not use an apostrophe to show genitive possession (Karls Haus, Marias Buch), but there is an exception to this rule when a name or noun ends in an s-sound (spelled -s, ss, -ß, -tz, -z, -x, -ce). In such cases, instead of adding an s, the possessive form ends with an apostrophe: Felix’ Auto, Aristoteles’ Werke, Alice’ Haus. – Note: There is a disturbing trend among less well-educated German-speakers not only to use apostrophes as in English, but even in situations in which they would not be used in English, such as anglicized plurals (die Callgirl’s).

B. Like English, German also uses the apostrophe to indicate missing letters in contractions, slang, dialect, idiomatic expressions or poetic phrases: der Ku’damm (Kurfürstendamm), ich hab’ (habe), in wen’gen Minuten (wenigen), wie geht’s? (geht es), Bitte, nehmen S’ (Sie) Platz!

But German does not use an apostrophe in some common contractions with definite articles: ins (in das), zum (zu dem).

3. Komma (Comma)

A. German often uses commas in the same way as English. However, German may use a comma to link two independent clauses without a conjunction (and, but, or), where English would require either a semicolon or a period: In dem alten Haus war es ganz still, ich stand angstvoll vor der Tür.But in German you also have the option of using a semicolon or a period in these situations.

B. While a comma is optional in English at the end of a series ending with and/or, it is never used in German: Hans, Julia und Frank kommen mit.

C. Under the reformed spelling rules (Rechtschreibreform), German uses far fewer commas than with the old rules. In many cases where a comma was formerly required, it is now optional. For instance, infinitive phrases that were previously always set off by a comma can now go without one: Er ging(,) ohne ein Wort zu sagen. In many other cases where English would use a comma, German does not.

D. In numerical expressions German uses a comma where English uses a decimal point: €19,95 (19.95 euros) In large numbers, German uses either a space or a decimal point to divide thousands: 8 540 000 or 8.540.000 = 8,540,000 (For more on prices, see item 4C below.)

4. Gedankenstrich (Dash, Long Dash)

A. German uses the dash or long dash in much the same way as English to indicate a pause, a delayed continuation or to indicate a contrast: Plötzlich — eine unheimliche Stille.

B. German uses a dash to indicate a change in the speaker when there are no quotation marks:Karl, komm bitte doch her! – Ja, ich komme sofort.

C. German uses a dash or long dash in prices where English uses double zero/naught: €5,— (5.00 euros)