In German, some verbs separate into two parts when used in present tense. While that might sound weird—to take a word and break it apart even for normal use—we do the same thing in English. In English, they’re called “phrasal verbs.”

In German, some verbs separate into two parts when used in present tense. While that might sound weird—to take a word and break it apart even for normal use—we do the same thing in English. In English, they’re called “phrasal verbs.”

For example, consider what you do with a library book: do you check it? No. You check it out. You can also check for the library book while you’re browsing through the aisles (you know, to make sure it’s there). And when you bring it back, you make sure it gets checked back in—once the librarian has checked it over to make sure you haven’t written all over it in crayon or spilled beer onto the cover.

Just by adding one preposition (a word that shows the relationship between two things, such as in, on, at, over, under, etc.), we can change the meaning of the verb. In German, plenty of verbs are made of a prefix (often a preposition) and a core verb. When a prefix is added to a core verb, the meaning changes.

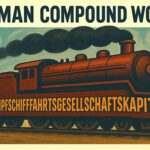

When you start with a German separable verb, referred to in German as a “trennbares Verb” (separable verb), you might begin working with it in the infinitive form. Or at least you should if you prefer to keep life simple.

For example, aufstehen (“stand up” or “get up”) is literally “upstand” or “upget” since the preposition is stuck on the front. If you want to talk about what time you get up in the morning, you would split that “auf-” off from the front of the trennbares Verb, “aufstehen,” then you would put it at the end of the sentence and conjugate “stehen” like you normally would:

Ich stehe um sieben Uhr auf. (I get up at seven o’clock.)

Let’s do another one with the verb zuhören (to listen to).

If you want to say “I listen to you,” separate the “zu-” from the front and put it at the end, again conjugating the main verb, “hören,” according to the subject:

“Ich höre dir zu.” (I listen to you.)

Also, remember that in this case we say “dir” and not “dich” or “du” because we’re using the dative case. What a lovely, easy language!

As a final, common example, if you call your friend, you use the verb “anrufen” (to call), which becomes:

“Ich rufe meine Freundin an.” (I call my friend.)

How do you know if a prefix or verb is separable?

Fortunately, you don’t have to go through and memorize every verb and whether or not it’s a separable verb. You can just memorize which prefixes come off and which ones don’t. And if you really want to keep your required efforts to a minimum, you just need to remember which verb prefixes don’t separate; that list is shorter and easier to remember.

Fortunately, you don’t have to go through and memorize every verb and whether or not it’s a separable verb. You can just memorize which prefixes come off and which ones don’t. And if you really want to keep your required efforts to a minimum, you just need to remember which verb prefixes don’t separate; that list is shorter and easier to remember.

The following are non-separable prefixes:

be-, ent-, emp-, er-, ge-, miss-, ver-, and zer-

That’s it. You’re done. No, really, it’s that simple. Seriously!

For example:

Kaufen (to buy): “Ich kaufe einen Apfel.” (I buy an apple.) No prefix. Easy.

Einkaufen (to shop or to buy): “Ich kaufe einen Apfel ein.” (I buy an apple.) Notice how that prefix isn’t on our list of separable prefixes? Then pop that ein off and stick it on the end.

Verkaufen (to sell): “Ich verkaufe einen Apfel.” (I sell an apple.) Here we have the prefix ver-, which is on our list of nonseparable prefixes, so we leave it right where it is.

One side note: the difference between kaufen and einkaufen can sometimes be confusing, so you might want to read a bit more about that.

And just for fun, here’s another example:

Sprechen (to speak): “Wir sprechen Deutsch.” (We speak German.) No prefix, no problem.

Absprechen (to agree): “Wir sprechen den Preis ab.” (We agree on the price.) Here we have a prefix that isn’t on our list of inseparable prefixes, ab, so we take it off the verb and stick it at the end.

Versprechen (to promise): “Wir versprechen, nur Deutsch zu sprechen.” (We promise to only speak German.) That there ver- is a non-separable prefix so we leave it alone.

How Do You Know Where to Separate Separable Verbs and What to Do with the Two Halves?

At this point, you probably have a pretty good handle on where the separation goes when you’re dividing up separable verbs, but in case you’d like to check out a detailed list of prefixes and their associated meanings, you’ll know exactly where to cut the verb or where to insert the “ge-”.

At this point, you probably have a pretty good handle on where the separation goes when you’re dividing up separable verbs, but in case you’d like to check out a detailed list of prefixes and their associated meanings, you’ll know exactly where to cut the verb or where to insert the “ge-”.

The rule is always to separate between the prefix and the core verb.

Here’s a basic example:

“Ich habe es abgesprochen.” (I arranged it.)

See how the “ge-“ goes between the “ab-“ and the “gesprochen?” But by now you knew that already, right?

Just in case you want to make double sure, try this one:

“Die Milch ist abgelaufen.” (The milk has expired.)

A word on negation: If you want to negate separable verbs, put the “nicht” right before the prefix.

Zum Beispiel (for example), we would say “he washed his hands” as:

“Er wäscht sich seine Hände ab.”

If Herr Muster (Mr. Sample) is a bit of a slob, we can say:

“Er wäscht sich seine Hände nicht ab.”

(He doesn’t wash his hands off.)

Learning German doesn’t have to be hard. In fact, if you take it one step at a time it becomes almost effortless.

German separable verbs come easily after you have a good handle on a few core verbs and you know which prefixes separate. With that knowledge under your belt, you should be able to use separable verbs with confidence. And before you know it, your verb separation anxiety will be a thing of the past.