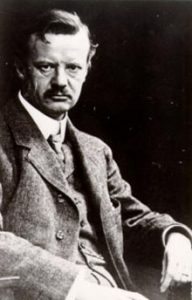

Hans Spemann (born June 27, 1869, Stuttgart, Württemberg – died Sept. 12, 1941, Freiburg im Breisgau, Ger.), German embryologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1935 for his discovery of the effect now known as embryonic induction, the influence exercised by various parts of the embryo that directs the development of groups of cells into particular tissues and organs.

Hans Spemann (born June 27, 1869, Stuttgart, Württemberg – died Sept. 12, 1941, Freiburg im Breisgau, Ger.), German embryologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1935 for his discovery of the effect now known as embryonic induction, the influence exercised by various parts of the embryo that directs the development of groups of cells into particular tissues and organs.

Spemann, initially a medical student, attended the universities of Heidelberg, Munich, and Würzburg and graduated in zoology, botany, and physics. He worked at the Zoological Institute of Würzburg (1894–1908), held a professorship at Rostock (1908–14), was director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology in Berlin (1914–19), and occupied the chair of zoology at Freiburg (1919–35).

Hans Spemann was born in Stuttgart, the eldest son of publisher Wilhelm Spemann and his wife Lisinka, née Hoffman. After he left school in 1888 he spent a year in his father’s business, then, in 1889–1890, he did military service in the Kassel Hussars followed by a short time as a bookseller in Hamburg. In 1891 he entered the University of Heidelberg where he studied medicine, taking his preliminary examination in 1893. There he met the biologist and psychologist Gustav Wolff who had begun experiments on the embryological developments of newts and shown that, if the lens of a developing newt’s eye is removed, it regenerates.

In 1892 Spemann married Klara Binder with whom he had two sons. In 1893–1894 he moved to the University of Munich for clinical training but decided, rather than becoming a clinician, to move to the Zoological Institute at the University of Würzburg, where he remained as a lecturer until 1908. His degree in zoology, botany, and physics, awarded in 1895, followed study under Theodor Boveri, Julius Sachs and Wilhelm Röntgen.

For his Ph.D. thesis under Boveri, Spemann studied cell lineage in the parasitic worm Strongylus paradoxus, for his teaching diploma, the development of the middle ear in the frog.

Spemann’s name will always be associated with his work on experimental embryology. He made himself a master of micro-surgical technique and, working on the relatively large eggs of amphibians he discovered in 1924, together with Hilde Mangold, the existence of an area in the embryo, the portions of which, upon transplantation into an indifferent part of a second embryo there organized (induced) secondary embryonic primordia. The name «organizer center» or «organizer» was therefore given by him to those parts. For this discovery of the organizer effect in embryonic development, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1935.

Later Spemann showed that different parts of the organization center produce different parts of the embryo. The anterior parts of it tend to produce parts of the head, and the posterior parts of it parts of the tail. Further, tail organizers, when they are grafted into the head region of another embryo, may produce heads instead of tails, the reason being that they are influenced by the head organizer in their new environment.

Earlier Spemann had transplanted the optic cups of new embryos into the outermost layer of the region of the abdomen and had found that they induced the production, in this new situation, of a lens of the eye. This was interpreted as being evidence of the existence of secondary organizers which operate after the induction exerted by the primary organizer has been completed.

By these and other experiments of a similar kind Spemann laid the foundations of the theory of embryonic induction by organizers, which led later to biochemical studies of this process and the ultimate development of the modern science of experimental morphogenesis. He described his researches in his book Embryonic Development and Induction (1938).

Spemann died at Freiburg on September 9, 1941.