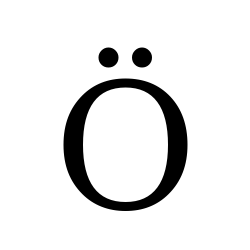

The German alphabet consists of 26 characters plus 3 umlauts: ä, ö and ü. The two dots above the letters do not indicate an accentuation or emphasis of the syllable (as for instance accent-bearing letters in Spanish or French). Umlauts are used as independent characters in the German language.

The German alphabet consists of 26 characters plus 3 umlauts: ä, ö and ü. The two dots above the letters do not indicate an accentuation or emphasis of the syllable (as for instance accent-bearing letters in Spanish or French). Umlauts are used as independent characters in the German language.

Whenever the use of umlauts is not possible (e.g. for technical reasons, in email addresses or names of websites), umlauts are indicated by the following combinations:

“ae” = ä, “oe”= ö, “ue” = ü.

Here are 8 facts you should know about the umlaut:

1. The word “umlaut” comes from one of the Grimm Brothers.

Jacob Grimm was not only a collector of fairy tales (along with his brother Wilhelm), but also one of the most famous linguists ever. In 1819 he described a sound-change process that affected the historical development of German. He called it umlaut from um (around) + laut (sound).

2. “Umlaut” is originally the name for a specific kind of vowel mutation.

Technically, “umlaut” doesn’t refer to the dots, but to the process where, historically, a vowel got pulled into a different position because of influence from another, upcoming vowel.

3. Mimicking that mutation process is a great way to learn to pronounce the umlaut.

Try this: make a u sound (an “oo”). Now imagine there’s an i-sound (an “ee”) coming up. Keep your lips completely frozen in u position while you try to say “ee” with the rest of your mouth. You should feel the body of your tongue move forward and up in your mouth. Hold that u sound with your lips though! Good. That’s an ü.

Not working? Trying pinging back and forth: oo-ee-oo-ee-oo-ee-oo-ee … now freeze your tongue position in “ee” and only move your lips back to “oo.”

(Start with “ah” for ä and “oh” for ö.)

4. English was also affected by the umlaut mutation.

Ever wonder why the plural of “mouse” is “mice”? Blame umlaut. Way, way back in a time before English had branched off from other Germanic languages, plurals were formed with an –i ending. So mouse was “mus”, and mice was “musi”. That plural –i pulled the u forward into umlaut. Later, the –i plural ending disappeared and a whole bunch of other sound changes happened, but we are left with the echo of that mutated vowel in mouse/mice, as well as in foot/feet, tooth/teeth, and other irregular pairs.

5. Umlauts weren’t always written as dots above a vowel.

Since the Middle Ages, umlauted vowels have been indicated in various ways in German. Before the two-dot version became the standard in the 19th century, it was usually written as a tiny “e” above the vowel.

It is still sometimes written with an e next to the vowel, for example, Muenchen for München, or schoen for schön.

6. An artificial language full of umlauts became hugely popular in the 1880s.

A German priest named Johann Schleyer invented a universal language he called Volapük. It was based on simplified European roots and was meant to be logical and easy to learn. It was chock-full of umlauts: “love” was löf, “smile” was smül, and “speak” was pük. Many people did learn it, and by 1889 there were over 200 Volapük clubs around the world and 25 Volapük journals. Even people who didn’t learn it had heard of it. But supporters thought it would have a better chance of succeeding internationally if it lost the umlauts. Schleyer refused. He said that “a language without umlauts sounds monotonous, harsh, and boring.” Infighting over umlauts and other proposed reforms led to a schism and, ultimately, to the decline of Volapük.

7. Heavy Metal Umlauts don’t look so heavy metal to umlaut users.

Beginning with Blue Öyster Cult in the early ’70s, heavy metal bands started using the umlaut to signal a badass hard rock attitude. To Americans the umlaut had a harsh, Teutonic look to it and Mötley Crüe, Motörhead, Queensrÿche, and dozens of other bands (listed on the Metal Umlaut Wikipedia page) tried to impart a little gothic scariness through randomly scattered pairs of dots. The dots didn’t have quite the same effect in umlaut-using countries, where the umlaut signifies vowel qualities of softness, highness, lightness and roundedness.

8. Typing Umlauts on a PC and Mac is easy.

On a PC (Windows):

The fail-safe method using the ALT-key:

• Number Lock should be ON

• Use the left-side ALT key (for most keyboards; try the right if it doesn’t work)

• Hold down the ALT key and type a number on the number pad as follows (while holding the ALT key down). When you release the ALT key, you will have the following character:

ALT 0223 = ß

ALT 0228 = ä

ALT 0246 = ö

ALT 0252 = ü

ALT 0196 = Ä

ALT 0214 = Ö

ALT 0220 = Ü

On a Mac:

• Use the OPTION key. Hold down OPTION and push ‘s’ to get ß.

• For the umlauted characters, hold down OPTION and push ‘u’. Release OPTION, then type the desired base letter (a, o, u, A, O, or U). The umlaut will appear over the letter you typed.

• (So to type ü, you should hold down OPTION, press u, then release OPTION and press u again.)