When we think about what binds a nation together, language is often at the heart of the answer. In Germany’s case, this is especially true. Long before there was a unified German state, there was a German language – or rather, many variations of it – serving as a cultural glue across fragmented territories. From Romantic poets to 19th-century nation-builders, from Luther to modern politicians, German has shaped how people think about identity, belonging, and what it means to be part of a common story.

This article explores how the German language evolved into a powerful tool of national unity – through literature, education, media, and politics – and why its role in shaping collective identity continues to matter today.

Before the Nation: Language Without Borders

For centuries, what we now call Germany was a collection of duchies, kingdoms, and free cities within the Holy Roman Empire. There was no single German government, no single flag – but the idea of a shared language was already forming.

The various German dialects spoken across Central Europe reflected regional identities, but the written word began to serve as a cultural bridge. Thanks to Martin Luther’s Bible translation in the 16th century, a version of written German began to spread across territories that otherwise had little in common.

➡️ Related reading: Luther’s Language Legacy: How One Translation Shaped German

The Romantic Era: Language as Soul of the Nation

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, German thinkers and poets began to explore language as the essence of national identity. Figures like Johann Gottfried Herder argued that each people (Volk) had a unique Volksgeist – a national spirit – reflected in its language, folklore, and traditions.

This was a radical idea at the time. While empires focused on politics and dynasties, the Romantics suggested that language was the true foundation of belonging.

Writers like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller wrote in German not just as a medium, but as an affirmation of cultural identity. The popularity of German literature helped standardize spelling and syntax, creating a shared linguistic experience across regions.

Language as a Nation-Building Tool

By the mid-19th century, the idea of unifying the German-speaking peoples gained political traction. The drive for national unity – culminating in the founding of the German Empire in 1871 – relied heavily on language.

German became the official language of education, law, and government. School systems were expanded to ensure all citizens learned Hochdeutsch (Standard German), even in dialect-heavy regions like Bavaria or Saxony. Newspapers, textbooks, and military manuals all reinforced linguistic uniformity.

In a country still regionally diverse, language was the thread that could stitch the national fabric together.

The Rise of German Nationalism and the Role of Language

Language also became a tool of exclusion. In border regions like Alsace, Silesia, or South Tyrol, linguistic identity was tied to questions of loyalty. Was someone German because they spoke the language – or were they an outsider if they didn’t?

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the German language was used both to include and to marginalize. Germanization policies in Prussian-occupied Poland, for example, forced students to abandon their native languages in school.

Language was no longer just a cultural marker – it was a political weapon.

After World War II: Rebuilding Identity through Language

The horrors of the Nazi era forced a national reckoning – not just with politics, but with language itself. Propaganda had twisted German into a tool of dehumanization. After 1945, educators and writers had to rebuild trust in the language.

In both West and East Germany, language was used to construct competing versions of national identity:

- In West Germany, Hochdeutsch was promoted in schools and media to foster unity, while dialects began to fade in public life.

- In East Germany, the state used language to shape socialist identity, coining new terms and controlling vocabulary in line with ideology.

Writers like Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass used literature to reclaim the German language, giving voice to memory, resistance, and reflection.

German Language and Reunification

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the reunification of Germany in 1990 brought two German-speaking societies back together – each with their own cultural and linguistic developments.

Though both East and West used Hochdeutsch, differences in vocabulary, idioms, and speech patterns revealed subtle divides. Words like Plaste (plastic) in the East and Tüte in the West signaled where someone came from.

Reunification reignited questions: What kind of German should be spoken? Which dialects or regionalisms would survive? Could a common language bridge a once-divided nation?

Dialects and Identity: Still Relevant Today

Despite a century of linguistic standardization, regional dialects remain strong. In places like Bavaria, Swabia, and the Rhineland, speaking dialect is a badge of pride – and sometimes resistance to cultural homogenization.

Language continues to reflect layers of identity:

- National (as a German speaker)

- Regional (as a Bavarian or Berliner)

- Generational (as someone fluent in dialect or only in Hochdeutsch)

Today, many Germans are bilingual within their own language – switching between Standard German and dialect depending on context.

➡️ Related article: Dialects vs. Standard German: Why Both Still Matter

German Abroad: Language as Cultural Export

German is the most widely spoken native language in the European Union, and it has a strong international presence. From Namibia to Pennsylvania Dutch communities, from Swiss German to the Goethe-Institut’s global reach – German continues to shape identities far beyond Germany’s borders.

For second-language learners, speaking German often signifies a connection to cultural depth, intellectual tradition, and historical complexity. Language becomes not just a tool of communication, but a bridge to the German worldview.

➡️ Explore this more: Global German: How the Language Travels the World Today

Modern Politics and Language Use

In today’s political climate, language remains central to debates on identity, inclusion, and national values. Questions of immigration, integration, and citizenship often hinge on language proficiency.

Initiatives like Integration courses require newcomers to learn German not just for work, but to participate in social life. Politicians frame linguistic fluency as a prerequisite for being “truly” German – a notion that can unify or exclude, depending on how it’s applied.

At the same time, efforts to make German more inclusive – such as gender-neutral language forms – spark debate about tradition, progress, and who gets to shape the national tongue.

The German language has done more than evolve – it has built bridges, drawn lines, told stories, and shaped what it means to be German. From poets who defined its rhythm to politicians who used it to draw borders, German has been a key tool of identity construction.

In a globalized world where languages blur and shift, German remains deeply rooted in memory and meaning. It carries the weight of history – but also the promise of shared understanding.

Germany may be defined by regions, politics, and culture – but it is held together, still, by a language spoken in countless voices.

Related articles:

➡️ The Evolution of the German Language: A Cultural History

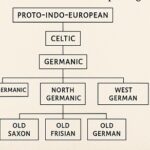

➡️ The Birth of German: From Proto-Germanic to Old High German

➡️ Luther’s Language Legacy: How One Translation Shaped German

➡️ Dialects vs. Standard German: Why Both Still Matter

➡️ Global German: How the Language Travels the World Today