The German language is more than just a way to say “Guten Tag.” It’s a living archive of Europe’s history – shaped by migrations, religious reform, literature, and the demands of political unity. From the tribal speech of wandering Germanic peoples to today’s global reach of Hochdeutsch, the story of German is a story of transformation, identity, and cultural resilience.

This guide takes you through the sweeping evolution of the German language – from its Indo-European roots to the formal standardization of Modern German. Along the way, we’ll uncover the fascinating interplay between dialect and nation, religion and language, local speech and international power.

From Proto-Germanic to Old High German: The Tribal Birth of German

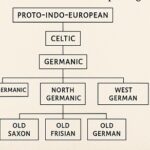

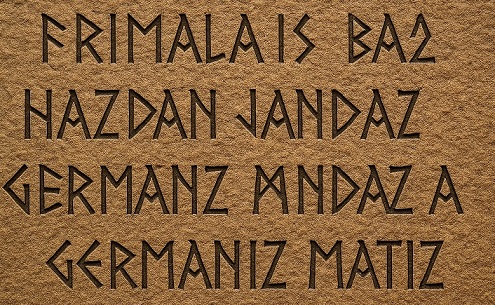

The origins of German go back to the Indo-European language family – a prehistoric mother tongue that splintered into many branches, including Celtic, Italic, Slavic, and Germanic.

Around 500 BCE, Germanic tribes began to form a distinct linguistic identity in what is now northern Europe. Their evolving dialects – known collectively as Proto-Germanic – laid the foundation for today’s German, English, Dutch, and Scandinavian languages.

One of the most crucial linguistic shifts in this period was Grimm’s Law – a sound shift that helps linguists trace the evolution of Germanic languages. For instance, Latin “pater” became “father” in English and “Vater” in German.

By the time of the Roman Empire, tribal dialects were widespread. The fall of Rome and the rise of Germanic kingdoms created even more linguistic fragmentation – and the birth of what we now call Old High German.

➡️ Deep dive: The Birth of German: From Proto-Germanic to Old High German

Middle High German: The Age of Knights, Poets, and Power

From roughly 1050 to 1350 CE, Old High German transitioned into Middle High German. This was the language of courtly love, epic poetry, and the fragmented Holy Roman Empire.

Works like the Nibelungenlied show us the literary style of the period – elegant, rhythmic, and filled with regional variation. Yet despite artistic flourishing, there was no single “German” language. Dialects dominated, and communication across regions was often difficult.

At this stage, German wasn’t standardized or centralized. Each region – Swabia, Bavaria, Saxony, Franconia – had its own spoken and written variant. Political disunity and strong local identities kept German fragmented well into the modern era.

Martin Luther and the Reformation: A Turning Point

Enter Martin Luther. In 1522, his translation of the New Testament into a common Saxon dialect was revolutionary. Not only did it make the Bible accessible to the masses, it also became the most influential act of linguistic standardization in German history.

Luther’s “Bible German” blended regional dialects with clarity, rhythm, and accessibility. With the help of the printing press, it spread widely – giving Germany a common written language before it had a unified nation.

Luther’s legacy went beyond religion – it shaped education, print culture, and everyday speech.

➡️ Read more: Luther’s Language Legacy: How One Translation Shaped German

Early New High German and the Rise of Standardization

From 1600 to the mid-1800s, German continued to evolve into what linguists call Early New High German. During this time, standard grammar books, dictionaries, and educational reforms began to appear.

The idea of a unified Hochdeutsch (High German) gained momentum. However, dialects remained strong in everyday speech. In fact, diglossia – the use of both dialect and standard language – remains a feature of German today.

Dialects vs. Standard German: A Linguistic Balancing Act

Even today, speaking “German” means navigating a wide range of regional forms:

- Bavarian (Bairisch)

- Swabian (Schwäbisch)

- Saxon (Sächsisch)

- Low German (Plattdeutsch)

- Franconian, Alemannic, Ripuarian, and many more

Hochdeutsch emerged from the southern dialects, especially in Saxony and Thuringia, and was eventually adopted by Prussia as the national standard in the 19th century.

Today, dialects are still spoken at home, in local pubs, and on regional TV. They’re cultural treasures – and symbols of identity.

➡️ See the spoke article: Dialects vs. Standard German: Why Both Still Matter

Language and Nation-Building in the 19th Century

Germany’s political unification in 1871 brought with it a stronger push toward linguistic unity. Nationalists like Johann Gottlieb Fichte argued that language shaped national spirit. Schools began teaching Hochdeutsch, newspapers adopted standard spelling, and regional differences were slowly ironed out.

The 19th and early 20th centuries also saw German emerge as a scientific and cultural powerhouse. German was the language of philosophy (Kant, Hegel), psychology (Freud), and music (Beethoven, Wagner).

➡️ Explore more in: From Poets to Politicians: German’s Role in Identity and Nation-Building

World Wars and the 20th Century: A Divided Language

The World Wars fractured Germany politically, and also linguistically. In East Germany, Russian influences crept into everyday vocabulary. In the West, English loanwords became more common.

Reunification in 1990 brought renewed debate about standard usage, orthographic reform, and linguistic identity. Meanwhile, the German-speaking world continued to grow outside Germany: Austria, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Liechtenstein, and parts of Belgium and northern Italy all used forms of German.

Modern Hochdeutsch: Education, Media, and Global Reach

Today, Standard German is used in schools, business, and media – but dialects continue to flourish. The language has embraced international influence, with new words from English (das Handy, downloaden, googeln) entering everyday use.

Digital communication has also led to slang innovation and code-switching among younger Germans. But the core structure of the language remains remarkably stable.

German is now the most spoken native language in the EU, and the third most taught foreign language worldwide.

➡️ Discover more in: Global German: How the Language Travels the World Today

Key Takeaways

- German evolved from tribal Proto-Germanic roots into today’s standardized Hochdeutsch

- Luther’s Bible was a linguistic turning point, shaping written German across regions

- Dialects continue to coexist with Standard German, offering cultural richness

- Language has always been a tool of German identity, education, and unification

- Today, German is a global language with deep historical roots and growing international relevance

Explore the Full Language Series

➡️ The Birth of German: From Proto-Germanic to Old High German

➡️ Luther’s Language Legacy: How One Translation Shaped German

➡️ Dialects vs. Standard German: Why Both Still Matter

➡️ From Poets to Politicians: German’s Role in Identity and Nation-Building

➡️ Global German: How the Language Travels the World Today

➡️ Du or Sie? Navigating Formality in German Conversation