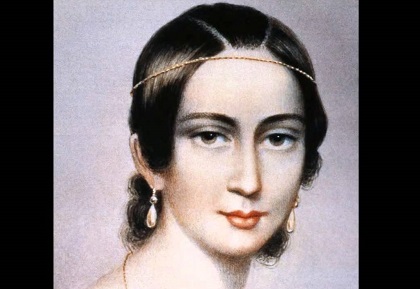

Clara Schumann was trained from the age of 5 with her father, the well-known piano pedagogue Friedrich Wieck. Prior to beginning her lessons, young Clara had only uttered her first words some time between 4 and 5 years old. In fact, she described herself as understanding as little as she spoke and as having disinterest in all that was passing around her, a condition that was not “entirely cured” – as she put it – until she was 8 years old. Clara Schumann’s pattern of delayed speech and subsequent virtuosity is shared by other famous late-talkers such as fellow pianist Arthur Rubinstein, physicists Albert Einstein and Richard Feynman, and mathematician Julia Robinson among others.

Clara Schumann was trained from the age of 5 with her father, the well-known piano pedagogue Friedrich Wieck. Prior to beginning her lessons, young Clara had only uttered her first words some time between 4 and 5 years old. In fact, she described herself as understanding as little as she spoke and as having disinterest in all that was passing around her, a condition that was not “entirely cured” – as she put it – until she was 8 years old. Clara Schumann’s pattern of delayed speech and subsequent virtuosity is shared by other famous late-talkers such as fellow pianist Arthur Rubinstein, physicists Albert Einstein and Richard Feynman, and mathematician Julia Robinson among others.

Clara Schumann had a brilliant career as a pianist from the age of 13 up to her marriage. Her marriage to Schumann was opposed by her father. She continued to perform and compose after the marriage even as she raised seven children. The eighth child died in infancy. In the various tours on which she accompanied her husband, she extended her own reputation further than the outskirts of Germany, and it was thanks to her efforts that his compositions became generally known in Europe. Johannes Brahms, at age 20, met the couple in 1853 and his friendship with Clara Schumann lasted until her death. J. Brahms helped Clara Schumann through the illness of her husband with a caring that bordered on love. Later that year, she also met violinist Joseph Joachim who became one of her frequent performance partners. Clara Schumann is credited with refining the tastes of audiences through her presentation of works by earlier composers including those of Bach, Mozart, and L.v. Beethoven as well as those of Robert Schumann and J. Brahms.

Clara Schumann often took charge of the finances and general house running due to Robert’s inclination to depression and instability. Part of her responsibility included making money, which she did performing – often Robert’s music. She continued to play not only for the financial stability, but because she wished not to be forgotten as a pianist. She had grown up performing and desired to continue performing. Robert, while admiring her talent, wanted a traditional wife to bear children and make a happy home, which in his eyes and the eyes of society were in direct conflict with the life of a performer. Furthermore, while she loved touring, Robert hated it and preferred to sit at the piano and compose.

From the time of her husband’s death she devoted herself principally to the interpretation of her husband’s works. But when she first visited England in 1856, the critics received Robert’s music with a chorus of disapproval. She returned to London in 1865 and continued her visits annually, with the exception of four seasons, until 1882. She also appeared there each year from 1885 to 1888. In 1878 she was appointed teacher of the piano at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt am Main, a post she held until 1892, and in which she contributed greatly to the improvement of modern piano playing technique.

From the time of her husband’s death she devoted herself principally to the interpretation of her husband’s works. But when she first visited England in 1856, the critics received Robert’s music with a chorus of disapproval. She returned to London in 1865 and continued her visits annually, with the exception of four seasons, until 1882. She also appeared there each year from 1885 to 1888. In 1878 she was appointed teacher of the piano at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt am Main, a post she held until 1892, and in which she contributed greatly to the improvement of modern piano playing technique.

Clara Schumann played her last public concert in 1891. She died five years later, in 1896, due to complications from a stroke. Besides being remembered for her eminence as a performer of nearly all kinds of pianoforte music, she was an impressive composer. Additionally, she was the authoritative editor of her husband’s works for the publishing firm of Breitkopf & Härtel. She is buried at Bonn’s Alter Friedhof old cemetery.