The crash of 1873 and the subsequent depression began the gradual dissolution of Bismarck‘s alliance with the National Liberals that had begun after his triumphs of 1866. In the late 1870s, Bismarck began negotiations with the economically protectionist Conservative Party and Center Party toward the formation of a new government coalition. Conservative electoral gains and National Liberal losses in 1879 brought a conservative coalition to power. Bismarck then abandoned his former allies in the National Liberal Party and put in place a system of tariffs that benefited the landed gentry of eastern Prussia–threatened by imports of cheaper grains from Russia and the United States–and industrialists who were afraid to compete with cheaper foreign manufactured goods and who believed they needed more time to establish themselves.

The crash of 1873 and the subsequent depression began the gradual dissolution of Bismarck‘s alliance with the National Liberals that had begun after his triumphs of 1866. In the late 1870s, Bismarck began negotiations with the economically protectionist Conservative Party and Center Party toward the formation of a new government coalition. Conservative electoral gains and National Liberal losses in 1879 brought a conservative coalition to power. Bismarck then abandoned his former allies in the National Liberal Party and put in place a system of tariffs that benefited the landed gentry of eastern Prussia–threatened by imports of cheaper grains from Russia and the United States–and industrialists who were afraid to compete with cheaper foreign manufactured goods and who believed they needed more time to establish themselves.

Bismarck’s alliance with the Prussian landowning class and powerful industrialists and the parties representing their interests had profound social effects. From that point on, conservative groups had the upper hand in German society. The German middle class began to imitate its conservative social superiors rather than attempt to impose its own liberal, middle-class values on Germany. The prestige of the military became so great that many middle-class males sought to enhance their social standing by becoming officers in the reserves. The middle classes also became more susceptible to the nationalistic clamor for colonies and “a place in the sun” that was to become ever more virulent in the next few decades.

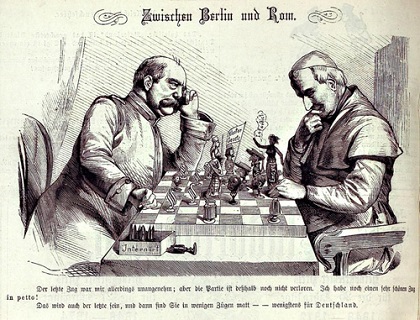

Kulturkampf (literally, “culture struggle”) refers to German policies in relation to secularity and the influence of the Roman Catholic Church, enacted from 1871 to 1878 by the Prime Minister of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck. The Kulturkampf did not extend to the other German states such as Bavaria. As one scholar put it, “the attack on the church included a series of Prussian, discriminatory laws that made Catholics feel understandably persecuted within a predominantly Protestant nation.” Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans and other orders were expelled in the culmination of twenty years of anti-Jesuit and antimonastic hysteria.

Kulturkampf (literally, “culture struggle”) refers to German policies in relation to secularity and the influence of the Roman Catholic Church, enacted from 1871 to 1878 by the Prime Minister of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck. The Kulturkampf did not extend to the other German states such as Bavaria. As one scholar put it, “the attack on the church included a series of Prussian, discriminatory laws that made Catholics feel understandably persecuted within a predominantly Protestant nation.” Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans and other orders were expelled in the culmination of twenty years of anti-Jesuit and antimonastic hysteria.

In 1871, the Catholic Church comprised 38% of the population of the German Empire. In this newly founded Empire, Bismarck sought to appeal to liberals and Protestants (61% of the population) by reducing the political and social influence of the Catholic Church.

Priests and bishops who resisted the Kulturkampf were arrested or removed from their positions. By the height of anti-Catholic legislation, half of the Prussian bishops were in prison or in exile, a quarter of the parishes had no priest, half the monks and nuns had left Prussia, a third of the monasteries and convents were closed, 1800 parish priests were imprisoned or exiled, and thousands of laypeople were imprisoned for helping the priests.

Bismarck’s program backfired, as it energized the Catholics to become a political force in the Centre party. The Kulturkampf ended about 1880 with a new pope willing to negotiate with Bismarck, and with the departure of the anti-Catholic Liberals from his coalition. By retreating, Bismarck won over the Centre party support on most of his conservative policy positions, especially his attacks against Socialism.

Related articles:

Otto von Bismarck: The Iron Chancellor

Imperial Germany – the Second Reich

Political Parties in Imperial Germany

The Economy and Population Growth in Germany

The Tariff Agreement of 1879 in Germany and Its Social Consequences

Foreign Policy in the Wilhelmine Era

Germany in World War I