A Country That Thinks in Proverbs Proverbs are the poetry of everyday life - short, punchy, and packed with centuries of wisdom. In Germany, they’re more than quaint sayings. They’re the go-to tools for expressing hard truths, sly warnings, and philosophical observations. Germans don’t just say what they mean. Often, they’ll let a well-placed … [Read more...]

Untranslatable German Words

Words the World Wishes It Had Every language has its quirks, but German might just be the master of invention when it comes to words that simply don’t translate. Ever longed for a place you’ve never been? Felt joy at someone else's misfortune (be honest)? Wished for a single word that could explain the awkwardness of two people dodging each … [Read more...]

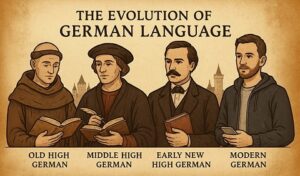

The Evolution of the German Language: From Old High German to Modern Dialects

This article explores the evolution of the German language, tracing its development from its early roots to the diverse regional dialects spoken today. Along the way, we will examine how historical milestones such as Martin Luther’s Bible translation, the printing press, and German unification helped shape modern German. The German language has … [Read more...]

Exploring the German Language Dialects

The German language, known for its precision and richness, is not a monolith but a mosaic of dialects that paint a colorful linguistic landscape across German-speaking regions. These dialects, deeply rooted in history and culture, offer a fascinating window into the diversity of the German-speaking world. In this comprehensive guide, we will … [Read more...]

Germany Exploration: Basic German Phrases for Travelers

Traveling to Germany soon? Whether you're heading to Berlin's urban jungles, the Black Forest's lush woods, or the Bavarian Alps, knowing a handful of basic German phrases can make your journey smoother and more enriching. While many Germans speak English, especially in tourist areas, attempting to communicate in their native tongue is always … [Read more...]

German Language: A Journey Through Linguistic Heritage, Structure, and Influence

The German language, known natively as Deutsch, is an Indo-European language and part of the larger West Germanic family that includes English and Dutch. It is primarily spoken in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Liechtenstein, and has around 95-100 million native speakers worldwide. It's one of the major languages of the European … [Read more...]

Common German Grammar Mistakes to Avoid

There is nothing wrong with making mistakes - the point is to learn from them when you make them so you can avoid making them again and come yet one step closer to proficiency. Two of the common errors that beginners typically make are: first, those garbled sentences that you can avoid only by learning whole new structures and making sure you … [Read more...]

How to Say Hello and Goodbye in German

Actually, the exact German equivalent to "hi" is, well, "hi". It’s not really German, as you might assume, but Germans adopted it and it’s quite usual among younger and less conservative people. From "hallo" to "na", learn the different ways to say “hello” in the German language. You’ll fit right in regardless of where you are in the country. 1. … [Read more...]

German Quotes to Help You Practice Your German

Quotes can make you laugh, cry, or think. They can help you find that tiny bit of truth that kept evading you. In other words, quotes evoke emotion. And when you have an emotional connection to something, you are more likely to remember it. Besides, it's a fun way to learn new words! “Dumme Gedanken hat jeder, aber der Weise verschweigt … [Read more...]

50 Common German Phrases That Are Hilarious in English

Although the German language may seem harsh and hard at first, it is filled with humorous expressions (many of them food-related). However funny expressions and phrases are at first, it's definitely worth learning a few. See for yourself! German Phrase Literal English Translation Meaning Jetzt geht's um die Wurst Now it goes … [Read more...]

- « Previous Page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- …

- 6

- Next Page »